Land Acknowledgement

This work would not have been possible without the guidance of Elder Grandmother Doreen Spence, along with the collaboration of various Indigenous communities, students, and philanthropic organizations, namely the Alberta Institute for Wildlife Conservation and the Calgary Foundation. In this article, we highlight student projects from the Research on Global Challenges course at the University of Calgary, which is situated in Treaty 7 territory, in the City of Calgary, known to the Blackfoot as Moh-kins-tsis, the Tsuut’ina as Guts’ists’I, and the Îyâxe Nakoda as Wîchîspa. In the spirit of respect, reciprocity, and truth, we honour and acknowledge the Blackfoot Confederacy comprising of the Siksika, Piikani, and Kainai First Nations, as well as the Tsuut’ina First Nation, and the Îyâxe Nakoda including the Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nations. We acknowledge that this territory is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3, within the historical Northwest Métis homeland. Finally, through our work and intentions, we strive to honour and celebrate the land, the four-leggeds, the swimmers, the crawlers, the winged ones, the plant people and all the diverse Nations with whom we were able to co-create this knowledge.

Introduction

Staff at the Alberta Institute for Wildlife Conservation (AIWC) bottle feed an orphaned moose calf. (Photo courtesy of aiwc.ca)

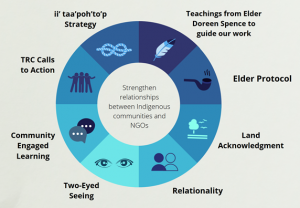

This paper serves to describe student projects that supported a community-campus partnership with the Alberta Institute for Wildlife Conservation (AIWC). The projects were guided by Elder teachings and ii’ taa’poh’to’p, the University of Calgary Indigenous Strategic Plan (Figure 1). As higher education progressively becomes more intertwined with community-based organizations, the need to develop partnerships between the two becomes more relevant and, if the relationship is reciprocal, further community-based outcomes can be supported (Thornton, 2009). Upon partnering with the student research teams, the AIWC indicated that they wanted to learn from local traditional knowledge keepers and work towards building relationships with Indigenous communities. The three student projects supported the needs of the AIWC by providing suggestions and literature reviews on forming relationships with Indigenous communities (community engagement team), by focusing on how to respectfully weave local traditional knowledge with AIWC educational programming (education team), and how to use social media for improved community engagement (social media team).

The community engagement team focused on connecting the AIWC to local Indigenous organizations. Animals hold a great significance within many Indigenous communities and are often involved in ceremonies, spiritual celebrations, and community relations (Robinson, 2014). Such animals include the porcupine (i.e. quills), eagle (i.e. feathers) and other birds of prey that the AIWC might have in their care. The team conducted and presented research and suggestions to aid the AIWC in initiating connections with the University of Calgary and surrounding Indigenous organizations.

Indigenizing education means co-preserving and co-creating a platform for the persistence of Indigenous peoples’ voices, history, and contemporary contributions (Sammel et al., 2020; Wildcat et al., 2014). Indigenous communities are overburdened by non-Indigenous people requesting publicly available information and taking limited resources away from communities. In partnership with the AIWC and in an effort to minimize the use of community resources, the education team researched Elder protocol, application of the Two-Eyed Seeing approach and compiled suggestions on how to respectfully incorporate Indigenous knowledge from Treaty 7 Nations into their education programs (Bartlett et al., 2012). Suggestions included integrating words from local Indigenous languages that describe animals and seasons, integrating learning techniques like sharing circles where everyone has the chance to speak (Pass The Feather Organization, 2021), as well as treating animals as teachers and partners in learning (McGinnis et al., 2019), and delivering courses through games developed by the Alberta Native Friendship Centres Association (Be Fit For Life, 2020).

This photo shows a gull involved in an oil spill. (Photo courtesy of aiwc.ca)

Social media engagement research was conducted to better understand how to create meaningful relationships between the AIWC and the communities they serve. A triangulation method was used to combine the analysis of numerical social media analytics while qualitative reflective conversations with AIWC staff helped guide the research. The findings from this data were then used to construct social media recommendations, a crisis response plan, and sample posts for the AIWC team to aid the organization in meeting their financial, operational, and community outreach goals.

The Calgary Foundation presented aspects of their reconciliation journey with the student teams by sharing how they work to strengthen relationships with Indigenous communities and transform the foundation’s colonial practices. When working towards reconciliation, they highlighted the importance of self-reflection and shifting power dynamics to create equitable relationships. Community-campus partnerships have the potential to integrate research from student-led projects to make changes and decolonize existing policies (Caldwell et al., 2015). Community-integrated experiences that follow respectful, reciprocal, relevant and responsible approaches (see 4Rs in Johnston et al., 2018), also have the benefit of bridging a critical gap between the needs of communities and the experiential learning needs of Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

Figure 1. This is the framework for student projects where teachings from Elder Doreen Spence guided each of the 4Rs and Elder protocol. The ii’ taa’poh’to’p strategy provided guidance to develop projects that would centre the TRC Calls to Action as well as meet the needs of our community partner (AIWC). Each project started with a land acknowledgement, and incorporated reflection on relationality and a Two-Eyed Seeing approach (adapted from Li & Kumar, 2021).

The 4 Rs

The rock people are the ancient beings. They have been here since time immemorial. They are the knowledge keepers. They know everything that happens upon the planet.

Elder Doreen Spence (E4E, 2021, 46:25)

The University of Calgary’s ii’ taa’poh’to’p (2017) strategy highlights the importance of reconciliation and giving space to Indigenous ways of knowing, doing, connecting, being and relating to decolonize non-Indigenous institutions. The 4Rs are principles that guided the work and intentions of each team through: respect that is embedded in humility and gratitude, all work being relevant to the community it aims to serve, contributing to the community through practices of reciprocity, and entering into caring and equitable relationships with all living and non-living beings (Johnston et al., 2018, p. 11-15). Together, the 4Rs form moral and ethical foundations for research and engagement with Indigenous peoples, communities, and ways of knowing (McGregor et al., 2018).

ii’ taa’poh’to’p (2017) outlines that, « educational institutions have a profound responsibility in initiating, securing and sustaining reconciliation » (p. 2), which is aligned with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 94 Calls to Action (TRC-CTA) to « redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation » (TRC, 2021). Our work with AIWC specifically aligns with TRC-CTA 62 that addresses governments, Indigenous people, and educators to create age-appropriate curriculum on Indigenous historical and contemporary contributions to Canada (TRC, 2021).

TRC-CTA 92 looks to the corporate sector in Canada, which could include not for profits (NFP), to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which « establishes a universal framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being” of Indigenous peoples globally (United Nations, 2007, para. 1). The UNDRIP can be used as a reconciliation framework where its principles centre: reciprocal relationships, obtain consent from Indigenous communities to develop projects, provide Indigenous people equitable access to jobs and reallocate resources equitably (de Gracia, 2021).

Respect

I said, ‘I can feel you but I can’t see you.’ I didn’t have my glasses or headlamp on, I was standing in the middle of nowhere. All of a sudden, the owl flew right in front of me and I could feel him fly past me. I said, ‘thank you for coming and visiting’.

Elder Doreen Spence (E4E, 2021, 39:07)

A foundational principle in ethical research practices when working with Indigenous communities is respect for human relationships, natural laws, and the more-than-human (Johnston et al., 2018; McGregor et al., 2018). The slogan, “nothing for us, without us” conveys the need for respect and involvement for marginalized groups in the implementation of policies (Herbert, 2017). Respect for Indigenous communities can be demonstrated through collaboration in designing programs and related funding, along with open dialogue between stakeholders (Elson et al., 2020; Villanueva, 2018). Additionally, the community engagement team suggested the development of a memorandum between organizations such as the AIWC and Indigenous communities outlining the guidelines of a respectful long-term relationship (Ball & Janyst, 2008).

Reciprocity

Unbalanced energies cannot be shared with entities around us; to engage in reciprocal relationships, balanced relationships require a ‘space of calmness, a place of centeredness, and focus to get the work done’.

Elder Doreen Spence (E4E, 2021, 9:00)

Reciprocity is a way of maintaining balance in research relationships and is critical to establishing mutual respect (McGregor et al., 2018). Philanthropists need to emphasize delivering their initiatives and learning as a two-way process that opens up a new level of understanding for both sides (Kirkness & Barnhardt, 2001). Such reciprocity is achieved when philanthropists make an effort to understand Indigenous ways of knowing, being, doing, and relating and Indigenous people are able to access and use the resources from philanthropic organizations in a way that benefits Indigenous communities. The research teams compiled sources for the AIWC that exemplify reciprocity through practices that follow proper Elder protocol and honour commitments made to Indigenous communities to foster respect. Organizations and foundations also have the responsibility to reduce burdens that do not benefit or serve Indigenous communities like completing onerous funding applications, managing demanding paperwork, and adhering to deadlines and reporting structures that are misaligned with community needs.

Relevance

You can influence one person at a time. Or, you can have a group of people that you can work with [to] pass sacred teachings on to them so that the future generations will have something to look forward to.

Elder Doreen Spence (E4E, 2021, 32:06)

Critical concerns about NFP organizations conducting ethical work with Indigenous communities involve forming authentic and sincere relationships; ensuring that the work, questions, outcomes, and research processes are all relevant to the community while holding institutions accountable to the general public (McGregor et al., 2018). However, research projects can often prioritize results over respecting Indigenous knowledge and community-identified priorities (Waters et al., 2021). Organizations are responsible for creating a space where Indigenous perspectives are welcomed and understood, and that lead to increased implementation of Indigenous-focused initiatives (Kirkness and Barnhardt, 2001). The education team made suggestions that were based on the concept of Two-Eyed Seeing, to encourage AIWC to see the significance of Indigenous pedagogies just as legitimate and valid as Western ways of knowing. This would allow the AIWC to implement both ways of knowing in their educational programs and ensure their work is relevant to all the communities they serve.

Relationality and Relationships

In the spring we get all the little crickets, all the little froggies, all the little beings, the birdies, they all sing this chorus of celebration. You sit in silence, and you listen to the birds chirping and breathe in the pure clean fresh air – that is medicine – that is healing! And we heal each other because we are supporting each other as a collective to make this place even more accessible for others.

…

I have a little shed here. A mother bear comes to sleep [in the shed] all the time. They love the energy. They feel safe.

Elder Doreen Spence (E4E, 2021, 53:54, 38:17)

Indigenous knowledge is relational in nature, and Indigenous research methodologies are “a process for establishing, strengthening, and coming into closer relationship with knowledge” (McGregor et al., 2018, p. 11). Building and maintaining trust is vital in all work that involves collaboration (Waters et al., 2021). Villanueva (2018) urges philanthropists to use practices that involve horizontal power structures and participatory grantmaking. It is important for philanthropists and NFPs to consider community-based approaches to giving when interacting with marginalized communities (Calgary Foundation, 2019).

Each research team had regular meetings with leaders from the AIWC and established a relationship where questions, openness and reciprocity were encouraged. From these conversations, the students were better able to understand the goals, struggles, and strategies of the AIWC. The community relationship team recommended that the AIWC have an open line of communication when it comes to providing gifts from animals such as quills or antlers for ceremony or art. Another recommendation was to consult and learn from Indigenous organizations and ask how, and if, they would like to be included in educational programs for wildlife conservation. The education team also suggested that the AIWC develop an advisory council of knowledgeable stakeholders, drawing upon the AIWC and local Indigenous communities to form long-term relationships.

Neonate orphaned animals require around the clock care to survive and have highly specialized diets and behavioral needs. (Photo courtesy of aiwc.ca)

Conclusion

The student research team’s projects support the identified needs of the AIWC in ways that adhere to the University of Calgary’s ii’ taa’poh’to’p strategy and align with the TRC Calls to Action. By offering suggestions that are specific to AIWC, the student research team has provided ideas and support for the AIWC to work towards reconciliation. The student teams also provided a working framework for how community-campus partnerships can foster reconciliation in animal conservation organizations.

Funding & Acknowledgements

Funding was kindly provided by the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning (University of Calgary) and by CEWIL Canada. We are incredibly grateful to Grandmother Elder Doreen Spence for her teachings and guidance on animal-human relationships, as well as for her support with the article. We are thankful to Tim Fox and Katie MacDonald from the Calgary Foundation for their thoughtful and supportive presentation to students. We very much appreciate the ongoing partnership and opportunity to collaborate with the Alberta Institute for Wildlife Conservation (AIWC), namely Holly Lillie who supported the research students throughout their projects.

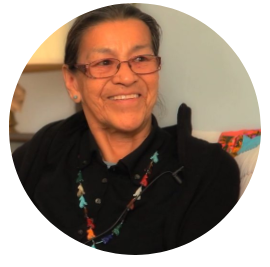

Known as Grandmother to many, Doreen Spence is a Cree Elder who was born and raised on the Good Fish Lake Reservation. She is also a member of the Saddle Lake Band as her father was from Saddle Lake. Grandmother Doreen is retired after having spent many years nursing in active treatment hospitals. Currently, she is an active Elder in Residence with the Cumming School of Medicine’s (CSM) Indigenous, Local and Global Health (ILGH) Office and mentors students and staff in the Alberta Indigenous Mentorship in Health Innovation (AIM-HI) Network and at Mount Royal and St. Mary’s Universities. Healing and wellness are her life-long legacy and she is honoured to have been recognized by so many for doing what she is so passionate about. She has received an honourary Bachelor of Nursing from Mount Royal University; been appointed to the Order of Canada; received the Indspire Award, the Alberta Centennial Medal, the Alberta Human Rights Award, the Chief David Crowchild Memorial Award, and the YWCA Woman of Distinction Award; and was one of the 1000 PeaceWomen nominated for the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize.

Known as Grandmother to many, Doreen Spence is a Cree Elder who was born and raised on the Good Fish Lake Reservation. She is also a member of the Saddle Lake Band as her father was from Saddle Lake. Grandmother Doreen is retired after having spent many years nursing in active treatment hospitals. Currently, she is an active Elder in Residence with the Cumming School of Medicine’s (CSM) Indigenous, Local and Global Health (ILGH) Office and mentors students and staff in the Alberta Indigenous Mentorship in Health Innovation (AIM-HI) Network and at Mount Royal and St. Mary’s Universities. Healing and wellness are her life-long legacy and she is honoured to have been recognized by so many for doing what she is so passionate about. She has received an honourary Bachelor of Nursing from Mount Royal University; been appointed to the Order of Canada; received the Indspire Award, the Alberta Centennial Medal, the Alberta Human Rights Award, the Chief David Crowchild Memorial Award, and the YWCA Woman of Distinction Award; and was one of the 1000 PeaceWomen nominated for the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize.

Find the full list of author biographies in the « For Further » section below.

Cet article fait partie de l’édition spéciale de Janvier 2022 : Philanthropie et la cause animale. Vous pouvez trouver plus d’informations ici

References

Ball, J., & Janyst, P. (2008). Enacting research ethics in partnerships with Indigenous communities in Canada: “Do it in a good way”. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 3(2), 33-51. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2008.3.2.33

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., & Marshall, A. (2012). Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2(4), 331-340.

Be Fit For Life. (2020). Move & Play through Traditional Games Lesson Plans. Be fit for life. http://befitforlife.ca/resources/move-and-play-through-traditional-games-cards

Caldwell, W.B., Reyes, A., Rowe, Z., Weinert, J., & Israel, B. (2015). Community partner perspectives on benefits, challenges, facilitating factors, and lessons learned from community-based participatory research partnerships in Detroit. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 9(2), 299-311. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2015.0031

Calgary Foundation. (2019). Strengthening relationships with Indigenous communities.

https://calgaryfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/StrengtheningRelationsImpactReport2019.pdf

de Gracia, N. (2021). Decolonizing conservation science: Response to Jucker et al. 2018. Conservation Biology, 35(4), 1321–1323. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13785

E4E: Educating for equity (2021, September 27). Elder Grandmother Doreen Spence: Indigenous Voices for Critical Education [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WcCqgxqwZJs

Elson, P. R., Lefèvre, S. A., & Fontan, J.M. (2020). Philanthropic foundations in Canada: Landscapes, Indigenous perspectives and pathways to change. Tellwell Talent.

Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous relations and northern affairs Canada. (2021, June 11). Delivering on truth and reconciliation commission calls to action. Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1524494530110/1557511412801.

Herbert, C. P. (2017, March 1). “Nothing About Us Without Us”: Taking action on Indigenous health. Insights (Essays). https://www.longwoods.com/product/24947

ii’ taa’poh’to’p. (2017). ii’ taa’poh’to’p together in a good way: A journey of transformation and renewal – Indigenous Strategy. Calgary, Alberta; University of Calgary.

Johnston, R., McGregor, D., & Restoule, J. P. (2018). Relationships, respect, relevance, reciprocity and responsibility: Taking up Indigenous research approaches. In Indigenous research: Theories, practices, and relationships (pp. 1–23). Introduction, Langara College.

Kirkness, V., & Barnhardt, R. (2001). The Four R’s – Respect, Relevance, Reciprocity,

Responsibility. First Nations and higher Eeucation. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education2/the4rs.pdf

Li, G., & Kumar, S. (2021). Indigenous friendship kit. Unpublished manuscript. Taylor

Institute for Teaching and Learning, University of Calgary.

McGinnis, A., Kincaid, A.T., Barrett, M.J., Ham, C., & Community Elders Research

Advisory Committee. (2019). Strengthening animal-human relationships as a doorway to Indigenous holistic wellness. Ecopsychology, 11(3), 162-173. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2019.0003

McGregor, D., Restoule, J., & Johnston, R. (Eds.). (2018). Indigenous research: Theories, practices, and relationships. Canadian Scholars.

Pass the Feather Organization. (2021). Benefits of using Sharing Circles. https://passthefeather.ca/sharing-circles/?v=e4b09f3f8402

Robinson, M. (2014). Animal Personhood in Mi’kmaq Perspective. Societies, 4(4), 672–688. doi:10.3390/soc4040672

Sammel, A., Whatman, S., & Blue, L. (2020). Indigenizing education: Lessons learned,

pathways forward. In A. Sammel, S. Whatman, & L. Blue (Eds.), Indigenizing Education (pp. 193–210). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4835-2_10

Spence, D. (Elder). (2021, October, 3). Saddle Lake Cree Nation. Treaty 7. Lives in Calgary. Oral Teaching. [Personal communication].

Thornton, C. H., Jaeger, A. J., & Beere, C. (2009). Understanding and enhancing the opportunities of community-campus partnerships. In Institutionalizing community engagement in higher education: The first wave of Carnegie Classified Institutions (pp. 55–63). essay, Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation

Commission of Canada: Calls to action. Government of Canada. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1524494530110/1557511412801

United Nations. (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples for

Indigenous peoples. United Nations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html

Villanueva. E. (2018). Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous wisdom to heal divides and restore balance. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Waters, S., El Harrad, A., Bell, S., & Setchell, J. M. (2021). Decolonizing primate conservation practice: A case study from North Morocco. International Journal of Primatology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-021-00228-0

Wildcat, M., McDonald M., Irlbacher-Fox S., Coulthard G. (2014). Learning from the land:

Indigenous land based pedagogy and decolonization. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3): 1-15.

Saskia Livingstone is a member of the Métis Nation of Alberta Region 3 and holds a Bachelor of Arts in Law and Society from the University of Calgary. She is a recipient of the PURE undergraduate research award and is currently working as a research assistant with Dr. Adela Kincaid. She worked alongside Dr. Adela Kincaid as a research coach for the UNIV 302 course focusing on humans, animals and the environment, which was supported by the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning at the University of Calgary.

Saskia Livingstone is a member of the Métis Nation of Alberta Region 3 and holds a Bachelor of Arts in Law and Society from the University of Calgary. She is a recipient of the PURE undergraduate research award and is currently working as a research assistant with Dr. Adela Kincaid. She worked alongside Dr. Adela Kincaid as a research coach for the UNIV 302 course focusing on humans, animals and the environment, which was supported by the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning at the University of Calgary.

Ginny Li is a Bachelor of Science student with a major of Biological Sciences. She is currently a research student under the mentorship of Dr. Adela Kincaid in the UNIV 302 course to find solutions for strengthening human-animal and environmental relationships. Her honours research is centered around conservation plant biology and pollinator interactions.

Ginny Li is a Bachelor of Science student with a major of Biological Sciences. She is currently a research student under the mentorship of Dr. Adela Kincaid in the UNIV 302 course to find solutions for strengthening human-animal and environmental relationships. Her honours research is centered around conservation plant biology and pollinator interactions.

Habeebah Adeladan is a 4th year Psychology major and health and society minor. She has had experience as a research assistant and as a student of the UNUIV 302 course at the University of Calgary. She will be completing an internship in the upcoming winter semester.

Nina Obiar is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Plant Biology with a minor in Anthropology at the University of Calgary. Over the summer, she was a research assistant that explored statistical models of plant biodiversity in British Columbia. She is currently a research coach in the Department of International Indigenous Studies; working alongside Dr. Adela Kincaid to explore animal-human relationships and land-based learning.

Nina Obiar is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Plant Biology with a minor in Anthropology at the University of Calgary. Over the summer, she was a research assistant that explored statistical models of plant biodiversity in British Columbia. She is currently a research coach in the Department of International Indigenous Studies; working alongside Dr. Adela Kincaid to explore animal-human relationships and land-based learning.

Shelly Kumar is currently a Bachelor of Arts Sociology major student at the University of Calgary with Gender, Family and Work concentration. She has been working as a research student over the past few months exploring animal-human relationships and Indigenous ways of knowing under Dr. Adela Kincaid and Saskia Livingstone’s supervision. She also holds a degree in nursing and is a dedicated nurse with extensive experience in both acute and community settings since past 6 years. She is also a volunteer at a community hospital and loves serving the community as a public servant. She is very passionate about working for and with the community.

Shelly Kumar is currently a Bachelor of Arts Sociology major student at the University of Calgary with Gender, Family and Work concentration. She has been working as a research student over the past few months exploring animal-human relationships and Indigenous ways of knowing under Dr. Adela Kincaid and Saskia Livingstone’s supervision. She also holds a degree in nursing and is a dedicated nurse with extensive experience in both acute and community settings since past 6 years. She is also a volunteer at a community hospital and loves serving the community as a public servant. She is very passionate about working for and with the community.

Sidra Tirmizi is currently working towards a degree in both Psychology as well as Biological Sciences. During the Fall 2020 semester at the University of Calgary, she has been working under the mentorship of Dr. Adela Kincaid in UNIV 302 to develop research with Indigenous communities and connection. A passionate advocate for mental health, Sidra spends her extracurriculars devoted to institutions of mental health.

Sidra Tirmizi is currently working towards a degree in both Psychology as well as Biological Sciences. During the Fall 2020 semester at the University of Calgary, she has been working under the mentorship of Dr. Adela Kincaid in UNIV 302 to develop research with Indigenous communities and connection. A passionate advocate for mental health, Sidra spends her extracurriculars devoted to institutions of mental health.

Margaret Anderson is a third-year student at the University of Calgary working towards her BSc in biological sciences and is minoring in management. She was a student under Dr. Adela Kincaid for UNIV 302 and worked on investigating effective social media use for the Alberta Institute for Wildlife Conservation with her research partner Habeebah Adeladan. She is involved in the veterinary and wildlife rehabilitation community, and this project was an amazing opportunity for her to combine her love for animals with helping non-profits to reach their goals.

Margaret Anderson is a third-year student at the University of Calgary working towards her BSc in biological sciences and is minoring in management. She was a student under Dr. Adela Kincaid for UNIV 302 and worked on investigating effective social media use for the Alberta Institute for Wildlife Conservation with her research partner Habeebah Adeladan. She is involved in the veterinary and wildlife rehabilitation community, and this project was an amazing opportunity for her to combine her love for animals with helping non-profits to reach their goals.

Isabelle Hunt is a 3rd year Political Science student with a minor in Law and Society at the University of Calgary. Her on-campus extracurriculars include participating as a student-athlete on the crew team and holding multiple positions within her sorority. She formerly worked for the Canadian Government in the House of Commons and is currently a student in UNIV 302.

Isabelle Hunt is a 3rd year Political Science student with a minor in Law and Society at the University of Calgary. Her on-campus extracurriculars include participating as a student-athlete on the crew team and holding multiple positions within her sorority. She formerly worked for the Canadian Government in the House of Commons and is currently a student in UNIV 302.