Limits and challenges of access to agroecological food – social technology and solidarity marketing at the Bem da Terra Virtual Market, Pelotas, Brazil

It is not news that agriculture has been facing profound changes. As a result of the Green Revolution, intensified by the voracity of agribusiness, countless countries, especially in the global South, started to use chemical pesticides and fertilizers in an accentuated way, with high losses to the health of producers and consumers, compromising the sustainability of human life on the planet. In addition to contaminated food, industrialized and ultra-processed foods also became part of the basic diet of most people. The consumption of such foods has led to widespread illness among the Brazilian population and provoked a reflection on the importance of building public policy strategies for food and nutritional security in the country, as well as self-managed alternatives for addressing the issue.

It is not news that agriculture has been facing profound changes. As a result of the Green Revolution, intensified by the voracity of agribusiness, countless countries, especially in the global South, started to use chemical pesticides and fertilizers in an accentuated way, with high losses to the health of producers and consumers, compromising the sustainability of human life on the planet. In addition to contaminated food, industrialized and ultra-processed foods also became part of the basic diet of most people. The consumption of such foods has led to widespread illness among the Brazilian population and provoked a reflection on the importance of building public policy strategies for food and nutritional security in the country, as well as self-managed alternatives for addressing the issue.

In this context, the disordered expansion of capitalism has been undermining food sovereignty and the human right to adequate nutrition (especially among the poorest) through the concentration of power in the hands of the few transnational corporations that control the production, distribution, commercialization and consumption of food. They dominate the technology and control the land, seeds and inputs. In this way, “agribusiness” manipulates governments and shapes policy to facilitate its expansion, to the detriment of the rights of the population and the protection of natural resources.

The study we report on here is based on the premise that the causes of this unprecedented food crisis are closely related to the contradictions of the capitalist mode of production; such contradictions cause the existing gap between the real production of food and the needs of the population, perversely affecting the distribution, marketing and consumption of food.

Conventional or Capitalist Technologies (CT) often have disastrous consequences, with destructive effects for the majority of the population and for the planet. CT aims at the accumulation of capital where workers are subjugated to the owners of the means of production, and the countries of the South are subjugated to the countries of the North, thus widening social inequalities. It thus shows “the tendency of contemporary capitalism to increasingly subject the production of knowledge to the logic of accumulation” (Dagnino, 2009, p. 97). Therefore, a movement for Social Technologies (ST) has emerged.

Social Technologies should: be adapted to small producers and consumers with low purchasing power; discourage capitalist organization, hierarchizing and dominating workers; be human-needs-oriented; foster the creative potential of producers and consumers; and “to be able to make economically viable enterprises such as popular cooperatives, land reform settlements, family farming and small businesses” (Novaes; Dias, 2009, p. 18-9).

In this sense, ST are more connected to the local reality, developing more appropriate responses to the problems of a given context. For societal transformation to occur, it is important to improve local techniques through a growth process that is carried out from within and not through external imposition. In summary, it is possible to conclude that, while CT is functional for large multinational companies, ST is directed towards collective production and not marketing.

Building another societal model is a challenge requiring great effort, but it is imperative. Through cooperation and reciprocity, a solidarity-based economy promotes this process of change, as it develops and disseminates Social Technologies as a force that transforms social reality. “Social Technology, in the context of the solidarity-based popular economy, places itself in a different paradigm than that in which technology is at the service of the market economy who’s base and engine are profitability” (Adams et al., 2011, p. 16).

In reaction to this troubling scenario, different initiatives for the production, commercialization and consumption of agroecological[1] foods can appear, and the consumer has acquired a special role in this process. Our work analyzed the limits and challenges in access to agroecological food from commercialization in the Virtual Fair of the Bem da Terra Network, consisting of a Responsible Consumption Group (RCG), which organizes producers and consumers. The research consisted of a critical qualitative study that combined bibliographic, document research with empirical data developed from participatory methodological strategies such as participant and activist observation.

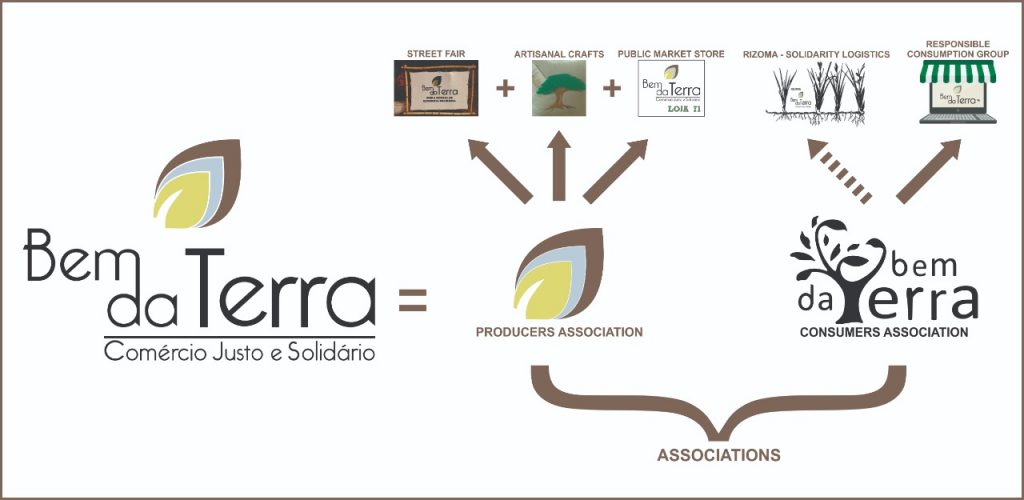

The “Bem da Terra Network” is a network of Solidary Economic Enterprises whose objective is to develop the Solidarity Economy[2] in the southern micro-region of Rio Grande do Sul – Brazil, disseminating practices and principles of fair trade and solidary consumption (Bem da Terra, 2018). It is configured as a complex network of production, distribution, commercialization and consumption of food. The two central actors of the network are the Producers Association (Bem da Terra Association) and the Consumers Association (Educational Association for Responsible Consumption Rede Bem da Terra), which assume the shared management of the Network.

The Bem da Terra Virtual Market was a strategic Social Technology developed to organize producers and consumers into compact solidary chains in order to strengthen the local economy. Through the Network, various products are marketed. Rural producers consume food in sufficient quantity and quality and supply the market with their surplus (consume what they need from their own production and sell the rest). The concept of Agroecology in the relevant literature goes beyond the question of the technique’s ecology-based benefits; it is evident that Agroecology is seen as much more than a technology, and more as a necessary and urgent political project, guided by political struggle and radical social transformation.

Despite the development of agroecological production within the Network, there is still a sensitive bottleneck that motivated this research: the expansion of access to agroecological foods, especially in relation to vulnerable or precarious populations. Unfortunately, the literature points out that only a small portion of the population consumes such foods. The general objective of the research was to identify the limits and challenges of access to agroecological food from the solidary commercialization of Virtual Fair. One of the specific objectives was to map the tools (popular STs) developed by the Network to expand solidarity marketing in the city of Pelotas, Brazil. A theoretical-political reflection constructed categories to support the analysis process: Solidarity Economy, Responsible Consumption and Social Technologies.

The results showed that the experience of the Virtual Fair contributed to improved access to agroecological food for the majority of active consumers, as they reported ease of access to food, while meeting the minimum criteria for continued Network association. However, for the population of the peripheral neighborhoods, access is still quite limited, suggesting the need for expansion. Furthermore, it was found that the actors involved in the dynamics are, to a large extent, critical, responsible and committed to the self-management process. Therefore, Bem da Terra Virtual Market is an experience, among many others under construction, that practices alternative forms of production and consumption, while aiming at social transformation through the reduction of inequalities and social injustices. This preliminary research highlights the need for more research into different social technology initiatives aimed at improving access to agroecological foods in order to better understand their limiting factors and improve access to all.

Bem da Terra Fair Trade Network – social actors and structures

Cet article provient du Hub International – Amérique Latine – Brésil

Adams, Telmo et al (2011). Tecnologia Social e Economia Solidária: desafios educativos. Revista Diálogo. Canoas, RS, N° 18, 2011. Available in:

<https://revistas.unilasalle.edu.br/index.php/Dialogo/article/view/101/118>.

Bem da Terra, (2018). <http://bemdaterra.org/>.

Dagnino, Renato (2009). Tecnologia Social: ferramenta para construir outra sociedade. 2 ed. Campinas, SP: Komedi.

Novaes, Henrique T.; Dias, Rafael (2009). “Contribuições ao Marco Analítico-Conceitual da Tecnologia Social”. In: DAGNINO, Renato. (Org). Tecnologia Social: ferramenta para construir outra sociedade. 2 ed. Campinas, SP: Komedi, p. 17-53.

Ripess (2020). Intercontinental network for the promotion

of social solidarity economy. Available in: http://www.ripess.org/what-is-sse/what-is-social-solidarity-economy/?lang=en

Tripathi, Nimisha; Singh, Ranjeet; Pal, Danielle & Singh, Raj. (2015). Agroecology and sustainability of agriculture in India: An overview. EC Agriculture. 2. 241-248. Available in: < http://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/416262/>

- Rocha, Miria (2019). Limites e desafios do acesso ao alimento agroecológico: a Feira Virtual Bem da Terra como estratégia de comercialização solidária. Pelotas, Brazil. Available in: <https://pos.ucpel.edu.br/ppgps/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/02/disserta%c3%a7%c3%a3o-m%c3%adria-raquiel-da-costa.pdf>

- Feira Virtual Bem da Terra vídeo. Available in:<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFZIqUM8j6M>

- Nunes, Tiago de Garcia; Gotardo, Solaine; Christ, Samara; Santos, Aline Mendonça; Della Vechia, Renato (2019). “Rede Bem da Terra: Produção Solidária, Consumo Responsável e Autogestão a partir da perspectiva extensionista do NESIC/UCPel”. Otra Economía Review, vol. 12, n. 21:219 – 230. Available in:

<https://revistaotraeconomia.org/index.php/otraeconomia/article/view/14789/9400>

[1] Agroecology is the application of ecological concepts and methodological design for long-term enhancement and management of soil fertility and agriculture productivity. It provides a strategy to increase diversified agro-ecosystem. It is benefiting from the incorporation of plant and animal biodiversity, nutrient recycling, biomass creation and growth through the use of natural resource systems based on legumes, trees, and incorporation of livestock (Nimisha et al., 2015).

[2] The Solidarity Economy (SE) is an alternative to capitalism and other authoritarian, state-dominated economic systems. In SE ordinary people play an active role in shaping all of the dimensions of human life: economic, social, cultural, political, and environmental. SE exists in all sectors of the agricultural economy: finance, distribution, exchange, consumption and governance. SE is not only about the poor, but strives to overcome inequalities, which includes all classes of society. SE has the ability to take the best practices that exist in our present system (such as efficiency, use of technology and knowledge) and transform them to serve the welfare of the community based on different values and goals (Ripess, 2020).