A Conundrum for Sustainability and Evaluating Philanthropy: How (and Whether) to Compare Environmental and Social Impacts

The United Nations has put forward a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, which cover a range of sectors and issues: the environment, health, quality of life, education, inequality, the economy, poverty, and conflict. Far from being concerned solely with matters of the natural environment, these goals embody a more holistic definition of sustainability. Unsurprisingly, all of these areas may be ones in which individual charities seek to do good. But what happens when we consider the intriguing overlap between charitable work across the sustainability spectrum (i.e. the topic of the June PhiLab newsletter) and evaluating philanthropy (i.e. the topic of the March PhiLab newsletter)? Specifically, how do we evaluate, or measure the impact of, work done in the environmental sector against work done in some other societal sector (e.g. health or poverty)? For example, how do we compare saving lives to saving forests?

The United Nations has put forward a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, which cover a range of sectors and issues: the environment, health, quality of life, education, inequality, the economy, poverty, and conflict. Far from being concerned solely with matters of the natural environment, these goals embody a more holistic definition of sustainability. Unsurprisingly, all of these areas may be ones in which individual charities seek to do good. But what happens when we consider the intriguing overlap between charitable work across the sustainability spectrum (i.e. the topic of the June PhiLab newsletter) and evaluating philanthropy (i.e. the topic of the March PhiLab newsletter)? Specifically, how do we evaluate, or measure the impact of, work done in the environmental sector against work done in some other societal sector (e.g. health or poverty)? For example, how do we compare saving lives to saving forests?

One response to the above questions could be that we simply do not have to compare charitable work in different sectors: all of it is important and all of it should be pursued. After all, the UN itself has set 17 different sustainable development goals and sees them as complementary rather than competitive. But the UN, by its very nature, must be concerned with all sectors at once, in a manner comparable to governments. Charities and non-government organizations, however, have no such restriction. They can specialize in a specific sector, which opens up all manner of situations in which comparative evaluation could take place. For instance, a charity might do work in more than one sector and thus an internal evaluation would help them to prioritize effectively between the different sectors. Governments and grantmaking organizations need to make decisions about the relative support to provide to different charitable causes and sectors. Charities in one sector (e.g. the environment) might be interested in advocating that their sector deserves higher tax incentives for giving, relative to other sectors (Ivany 2020). Of course, individual donors must also make decisions about which charities to support.

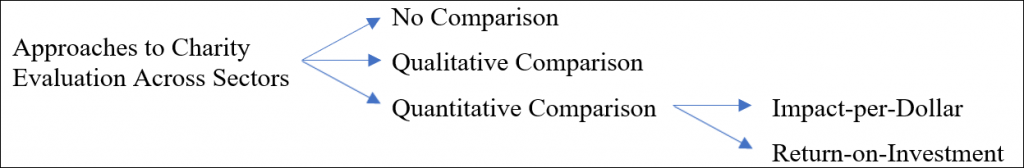

In this article, my position is that comparative evaluation of charities across sectors is an important consideration in philanthropy research. To initiate discussion on this issue, I suggest that there are essentially three approaches one could take: 1) simply not engage in comparative evaluation; 2) assess impacts qualitatively as a tool for subjective comparison; and 3) assess impacts quantitatively using analogous units of measurement for more direct comparison. This range of choices comprises a simple and tentative conceptual framework (based loosely on Polonsky and Grau 2011) for understanding comparative evaluation in philanthropy – each approach has advantages and disadvantages, and is suitable for different purposes. Individual charities and philanthropy research projects can consider which choice is most appropriate for their own interests, values, and needs. The remainder of the article explores each perspective using examples from charity evaluation groups, such as the “effective altruism” organizations introduced in the March PhiLab newsletter (Richards 2020).

The first approach to comparative evaluation across sectors is simply not to do it, to reject the very notion that different charitable sectors can or should be evaluated against each other. Indeed, some altruists may see life as sacred and intrinsically valuable, just as some environmentalists (Leopold 1949) may see the land as sacred and intrinsically valuable; attempting to quantify one in terms of the other or quantify either in dollar amounts may undercut the true value of both (Schumacher 1973).

From a practical – rather than philosophical – standpoint, “it would be unlikely that any social outcome criterion could be aggregated within sub-issues (such as environmental issues or animal issues), let alone aggregated across social issues” (Polonsky and Grau 2008), and thus some charity evaluation organizations simply sidestep the challenges of comparison across sectors. GiveWell, for example, starts its assessment process from the assumption that the most worthwhile charities are those that focus on the global poor, clarifying that it does not have the capacity to “review as many charities as possible” but rather “focuses on finding the best charities possible”. Similarly, Giving What We Can recommends one charity evaluation organization for donors interested in global health and development, and another for donors interested in animal welfare; there is no attempt to compare across sectors. There are thus good philosophical and practical reasons for the non-comparison approach, but it offers little guidance for situations where comparison is desired or required (e.g. see the second paragraph of this article above).

The second approach to comparative evaluation across sectors is to qualitatively measure the impacts of charities. This approach accepts that some charities are more effective than others and encourages comparison, but is wary of quantification, observing that some very important charities, such as those focused on cultural awareness, cannot easily translate their impacts into numerical terms (Pue 2016). One could collect descriptive information about the projects and successes of charity, gather anecdotes from community members or other stakeholders, consider “grades” or “scores” that charity evaluation organizations have provided on criteria like transparency and financial efficiency, or assess qualitative arguments about the advantages – or disadvantages – of choosing one charity or sector over another (e.g. in promotional and fundraising materials). Such “external” factors can be included alongside those that are more “internal” to the individual donor, government, or grantmaking organization considering the comparison, such as alignment with individual or organizational values and the desire to support local causes.

A good example of this comes from the Centre for Effective Altruism. It has four “funds” (i.e. sectors) for donors to consider in maximizing the impact of their giving: global health and development, animal welfare, long-term future, and effective altruism meta (i.e. promoting the principles of effective altruism itself). Each fund’s description includes reasons to donate to that fund and reasons why one might choose not to donate. For instance, donors who value certainty of impact may not be as interested in supporting the comparatively risky long-term future fund. Ultimately, the Centre provides a lot of qualitative information to help individual donors decide which sector to support, but does not explicitly make recommendations between the sectors (although, interestingly, the default allocation for a donation is 45%, 25%, 15%, and 15% to the above four funds respectively – this is not explained). The qualitative approach allows for a balance between individual judgement (or, as GiveWell would say, “worldview and intuitions”) and information, but it does not take full advantage of available evidence.

The third approach to comparative evaluation across sectors is to quantitatively measure impacts for a more direct comparison. It is premised on the observation that much time and effort is wasted on relatively inefficient charities or relatively ineffective causes, and sets out to identify the best charities and causes to support, using clear quantitative measures. I recognize two variants of the quantitative approach, impact per dollar and return on investment, the latter being more purely quantitative. The impact-per-dollar approach, similar to cost-effectiveness analysis from the field of economics, chooses some measure of impact or outcome from a charity’s activities (e.g. lives saved, acres of forest saved) and puts the cost in dollar terms. This results in a straightforward (though possibly oversimplified) measure of a charity’s effectiveness, but still leaves the actual comparison between measures as a matter of individual decision. For example, GiveWell suggests that some of its recommended charities can currently save the life of a child under 5 years of age in a developing country for about $500 US, while a very rough calculation based on CoolEarth’s annual report suggests that $500 US can currently protect about 1850 tonnes of stored carbon in at-risk rainforests – it would still be up to the individual grantmaking agency, donor, or government to decide on which cause it would be better to spend $500 (assuming they trust the calculations).

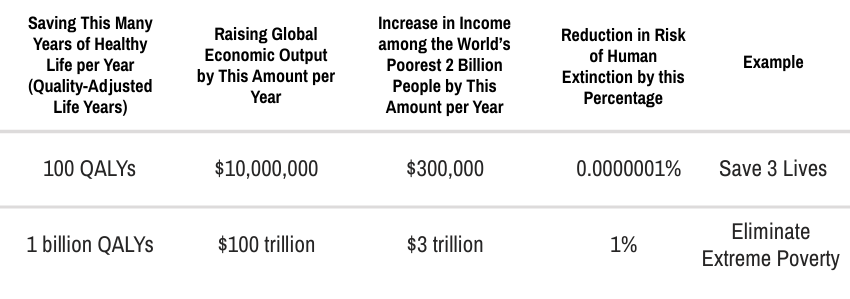

The return-on-investment approach, similar to cost-benefit analysis from the field of economics, goes one step further and also puts the impact or benefit in similar terms (e.g. dollars). A great example of this approach is 80000 Hours, an organization that attempts to determine which global issues are most worthy of support. It has assessed the severity, neglectedness, and solvability for dozens of such issues, justifying a score on each of the three criteria, which sum to an overall score and facilitate direct comparison. Topping out their list of the 11 most urgent issues is “risks from artificial intelligence” with a score of 27 out of 36 (i.e. severity score of 15 out of 16, neglectedness score of 8 out of 12, and solvability score of 4 out of 8). The list also includes “climate change (extreme risks)”, which is in the ninth position with a score of 20, but because the scale is logarithmic, is considered only 1/2000 as pressing as the artificial intelligence issue. 80000 Hours is transparent about its process, explaining its assumptions thoroughly and conceding that the scores are merely estimates. This includes an explanation of how it tentatively (i.e. with extreme uncertainty) translates the value of different “yardsticks” (i.e. measures of impact in different sectors). Below are selections from the top and bottom rows of its yardstick equivalencies table.

The main advantage of a quantitative comparison is that it provides clearer metrics for direct comparison of different charitable causes and sectors. It leaves less burden on individual interpretation, which may be prone to error and cognitive bias (e.g. supporting causes that are well known rather than causes with the most potential for impact). The main disadvantage is all the assumptions that must be built into the comparison, which perhaps should be matters for individual interpretation anyway. Certain charities or sectors might lack the resources to collect information on their impacts, or it might be difficult to quantify such impacts at all (Pue 2016), as discussed above. As well, “output” measures (e.g. number of meetings, number of reports, number of projects) are typically far easier to measure than the “outcome” measures (e.g. lives saved, trees protected, behaviours changed) typically used in quantitative comparison, which may require yet another layer of assumptions. Lastly, in light of this newsletter’s topic, I notice that environmental benefits are rarely explicitly considered in existing quantitative comparisons (e.g. even the full version of the above table contains no columns on environment-related yardsticks and no examples of environment-related actions); instead they are probably translated into terms of economic productivity in a manner similar to that of the Stern Review, which may not reflect their true value. Indeed, environmental causes seem to be quite rare on effective altruism lists; this may be appropriate, but as a scholar of the environment I am a little skeptical.

I believe that the above approaches to comparative evaluation of charities across sectors each have their uses. However, for scholars, organizations, and others encountering the necessity to engage in comparison, I would suggest defaulting to approaches in the “middle” of the spectrum (i.e. qualitative or impact-per-dollar) because they have more balanced advantages and disadvantages. One can then consider the more “extreme” approaches (i.e. return-on-investment or rejection of comparison) if appropriate. A possible hybrid approach, drawing on another technique from economics (i.e. multi-criteria analysis), would essentially amount to a comprehensive pro-con list including as many quantified costs and benefits as possible, but not in the same unit (e.g. both financial expenses and volunteer hours could be considered costs).

Another way to pursue “the best of both worlds” might be to link charities and causes together (Ivany 2020), especially given the integrative nature of sustainability. That is, a charity doing work in multiple sectors, on multiple causes, or that has multiple kinds of impacts, might emphasize one aspect in order to support others that are less marketable or which have less easily-quantified benefits. For example, the “oblique approach” in the Hartwell Paper (Prins et al. 2010) suggests that the increased distribution of small-scale renewable energy technologies would result in quality-of-life improvements for developing countries (a more marketable and quantifiable benefit) as well as climate change benefits (the underlying focus).

In conclusion, as we start to pay particular attention to environmental charities (e.g. here at PhiLab’s Atlantic Hub) and how to support them, we may need to appraise how environment-related work, outcomes, and benefits compare to other sectors, which may have a more established history of evaluation mechanisms. A spectrum of approaches, ranging from non-comparison to purely quantitative comparison, exists for us to consider in this regard. Rather than being an exercise in showing how one charity or sector is more deserving than others (or even in making a case for comparison to begin with), this should be an opportunity to come to terms with questions of comparison that will arise inevitably.

Ivany, M. (2020, June 24). Philanthropy in Newfoundland and Labrador: Supporting Environmental Charities and Non-Profits. Webinar for PhiLab Atlantic Hub.

Leopold, A. (1949). A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There. New York: Oxford University Press.

Polonsky, M. and Grau, S. (2008). Evaluating the Social Value of Charitable Organizations: A Conceptual Foundation. Journal of Macromarketing, 28(2), 130-140.

Polonsky, M. and Grau, S. (2011). Assessing the Social Impact of Charitable Organizations—Four Alternative Approaches. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 16(2), 195-211.

Prins, G., Galiana, I., Green, C., Grundmann, R., Hulme, M., Korhola, A. … Tezuka, H. (2010). The Hartwell Paper: A New Direction for Climate Policy after the Crash of 2009. Oxford: Institute for Science, Innovation and Society. Available at http://www.lse.ac.uk

/researchAndExpertise/units/mackinder/theHartwellPaper/Home.aspx

Pue, K. (2016, December 9). If You Are Giving to Charity This Holiday Season, Give Well

[Blog Post]. Huffington Post. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/kristen-pue/holiday

-charitydonation_b_13516588.html

Richards, G. (2020, April 12). Evidence-Based Policy Making, Policy Evaluation, and Effective Altruism: Considerations for a Research Project on Social Impact Measurement in Atlantic Canada [Blog Post]. PhiLab. Retrieved from https://philab.wpdev0.koumbit.net/home-blog/evidence-based-policy-making-policy-evaluation-and-effective-altruism-considerations-for-a-research-project-on-social-impact-measurement-in-atlantic-canada/

Schumacher, E. (1973). Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. London: Blond and Briggs.