“If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” – Lilla Watson, Indigenous Elder, Activist and Educator of Australia

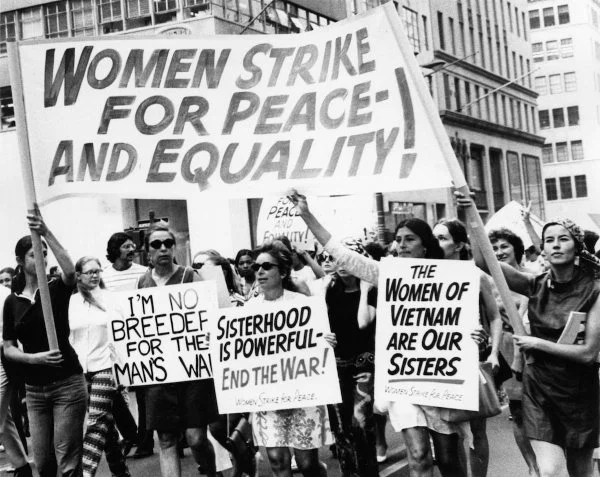

Women Strike for Peace – 1961

When I was a volunteer peer support worker on a sexual assault peer support phone line, we would receive calls from women and gender diverse individuals who would connect with us because we were one of the few free services that provide alternative, survivor-centred, anti-oppressive and feminist support. Even though the demand kept increasing for these community supports, new, stable or core funding was not the norm. Across different community- organizations I worked with, a significant amount of time, capacity and roles would need to be dedicated to fundraising, grant-writing and partnership development.

This theme of sustainability reverberates across community-based supports and grassroots groups. Many of these front-line roles that try to do more alternative community support are low pay, contractual or part-time. These pressures, among others, would contribute to competition for the meagre funds available for their ever-changing, complex communities in the face of increasing inequities. Despite the lack of sustainable funding, many of the community groups I organize with work unpaid, fund their own activities, and fundraise, finding these to be the most effective ways to do the work we want to do. There can be tensions as many funding opportunities can have stringent, restrictive or inaccessible guidelines, while grassroots groups do not want to restrict or minimize their mandates and missions of equity, social justice, anti-poverty or anti-violence. Feminist Grassroots and Transformative Visions of Change

An activist at heart and an emerging academic, I was hoping meaningful change could come by through these third sector spaces. The kind of liberatory and collaborative work that Lilla Watson speaks about when she says, “if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together”. While change can be seen, felt, experienced and measured in many different ways, the examples of shrinking, demanding and precarious work of support services such as the sexual assault support line were all too common. In particular, social and community work that uses more feminist and social justice approaches to support our communities struggle with the impacts of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is a theory of practices within the political economy that equates the well-being of humans with individual freedom based on rights to private property, free markets and free trade (Spolander et al., 2014). This system leads to prioritizing profit and productivity over equity, empowerment and community (Spolander et al.). Feminist Grassroots and Transformative Visions of Change

Violence Against Women (VAW) Protest in Chile Source: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-50557784

Within this system, social work practice is required to meet less regulated, and more privatized and economic models of capitalism. Social welfare and other social issues are subject to commodification in a competitive market. In attempts to maintain funding and operations, non-governmental organizations take responsibility for their community’s issues and many are forced to apply for service delivery funding under government administrative controls and requirements (Finley & Esposito, 2012; Spolander et al., 2014). There is a restructuring of social work education, job skills, and roles to mirror this system contributing to a lesser capacity to respond to the complexities of communities’ needs (Finley & Esposito, 2012; Spolander et al., 2014).

Social work positions in this model shift to a focus on risk and risk management and rely heavily on evaluation frameworks and oversight mechanisms to watch for inefficiencies (Spolander et al., 2014). Activism and advocacy are pushed to the wayside even as the pursuit of social justice is core to our ethics. Further, women occupy most of these social service worker roles, earning less for the same roles and being less likely to have full-year and full-time employment than men (HR Council for the Nonprofit Sector, 2013). So, the activists and community workers at heart often look at past and current alternatives to do the work we came here for.

As social workers in many of the third sector spaces where we are gatekeepers to key social and community supports, we are compelled to uphold social justice, self-determination and healing. This means we are meant to understand how power and oppression work. However, we are often faced with tensions from what our funding and administrative duties call us to do, and what our communities and those most marginalized call for. Feminist Grassroots and Transformative Visions of Change

We are fortunate to have the work of radical and intersectional feminist practice and analyses who show us how we can collectively imagine models of governance and funding for sustainable community work. Black, Indigenous, racialized and queer women and gender diverse peoples continue to pave the way in analyzing how systems of oppression work. They are re-claiming and re-imagining transformative change to create spaces outside of neoliberalism and other structures that can impede the most meaningful work. Social and community workers can follow Lilla Watson’s words and those of other Indigenous, women of colour and gender diverse activists, mobilizers, survivors, workers, farmers, community members and others resisting within the current system. This work would be transformative rather than perpetuate capitalism, patriarchy, colonialism, racism and other systems that cause violence.

In the sexual assault support centre, I learned the power of collective, grassroots and explicitly feminist, anti-colonial and anti-violence work. We worked collectively to learn about power, oppression and violence. We strived to support each other and our communities in responsive and flexible ways, and to promote education, accountability and advocacy that centred on those most impacted by violence and marginalization. How can funders and communities work together to strive for this transformative, collective work in sustainable and ethical ways? How can we (continue to) consider the complex realities of communities and feminist visions and desires in the work of volunteerism, giving and philanthropy?

Want to read more on Feminist Philanthropy? Check out our special edition on the subject here.

Vous voulez réagir à cet article? Écrivez-nous au courriel philab@uqam.ca , il nous fera plaisir de vous entendre!

Finley, L.L. & Esposito, L. (2012). Neoliberalism and the non-profit industrial complex: The limites of a market approach to service delivery. Peace Studies Journal, 5(3), 4-26.

Spolander, G., Engelbrecht, L., Martin, L., Strydom, M., Pervova, I., Marjanen, P., … Adaikalam, F. (2014). The implications of neoliberalism for social work: Reflections from six-country international research collaboration. International Social Work, 57(4), 301-314.

HR Council for the Nonprofit Sector. (2013). A profile of community and social service workers: National occupational classification (NOC 4212). Retrieved from: http://www.hrcouncil.ca/documents/LMI_NOC4212_1.pdf