If we compare how capitalism and democracy work, we observe that capitalism manages products and services with the objective of generating maximum financial profit. On the other hand, democracy manages diverse opinions with the objective of obtaining power through a majority vote. We can only conclude that access to power is expensive and that the majority of our leaders are part of the upper class.

(Our translation) Source: Ethicratia

Consultant for The Giving Practice, a consultant firm attached to the Philanthropy NorthWest foundation, Daniel Kemmis is the author of a summary analysis on the connections to be made between “philanthropy and democracy.” The author concludes his study with an invitation to operational and grantmaking foundations to be more politically involved actors to contribute to the challenge brought along by the rebirth of the democratic ideal. If his analysis can seem evident in the Trump era, is it truly a recent issue, and, especially, does it apply to the Canadian political scene and its philanthropic ecosystem?

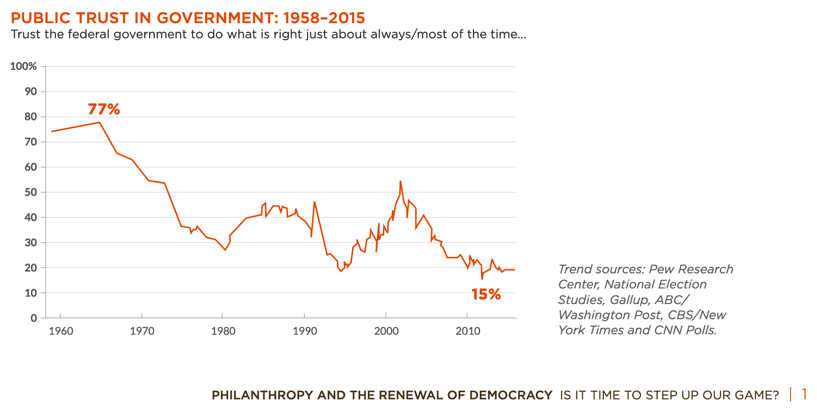

Daniel Kemmis’ contribution is impressive on two fronts. On the one hand, he presents an opinion on the state of affairs shared among the American philanthropic sector. Democracy is in crisis, which is fundamentally associated with the way the American State, in general, and large institutions are behaving towards a population in a state of poverty or social exclusion since the 1960s. To illustrate his point, he presents a summary graphic showing the evolution of the level of trust of the American population concerning the action posed by the central State. Throughout half a century, the decrease in confidence is outstanding. Whatever the generation, the ethnic group or their political stance, Republican or Democrat, despite a few spikes, nothing seems to be able to stop the bleeding. The steady decline continues throughout the decades.

By almost any measure, our institutions are falling short. Seemingly unrestrained partisanship, for example, is making it increasingly difficult and sometimes impossible to solve big problems, like controlling the national debt and bringing budget deficits within bounds, or addressing the challenges of climate change, immigration, poverty, or growing inequality. Deeply rooted institutional barriers also get in the way of problem solving, and they are intertwined with the problem of uncontrolled partisanship. The way congressional and legislative redistricting gets done, for example, helps to entrench partisanship and ideological polarization. (Daniel Kemmis, p. 1 (figure) et 2 (quote))

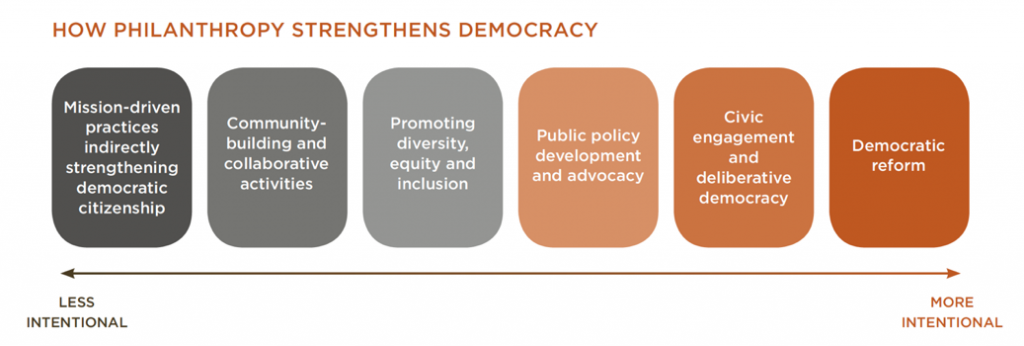

While this statement of democratic derailing is concerning, Daniel Kemmis remains optimistic and believes it is possible to rectify the situation. Grantmaking foundations, certainly not alone, but with others, could work towards revitalizing trust in the State and large institutions. The view that Kemmis brings to the strategies used by many American foundations allows him to identify diverse forms of action that would allow for a regain in trust in the democratic ideal. If they were to be adopted in their more extreme forms, they could favour not only a renewal of the democratic ideal but also an in-depth reform to its meaning and reach.

Philanthropy’s democracy-strengthening work may be pictured as a continuum, stretching from a broad and varied range of mission-driven philanthropic activities that unintentionally strengthen democratic citizenship, through more deliberate contributions to community-building, civic engagement and public policy work, culminating in a growing number of direct investments in democratic reform. From one end of this continuum to the other, philanthropy now has an opportunity to make timely and crucial contributions to restoring the health of our democracy. (Daniel Kemmis, p. vii, figure and quote)

Corroborating with Daniel Kemmis, Scott Nielsen and Loren McArthur, consultants for Arabella Advisors, have found a recent repositioning of both operational and grantmaking American foundations around the great challenge of revitalizing the democratic ideal.

Despite the presence of this trend, Daniel Kemmis’ optimism is nuanced by Scott London, a consultant for the Kettering Foundation and the Council of Foundations. In an essay called Our Divided Nation. Is There a Role for Philanthropy in Renewing Democracy?, he presents a recap of the main points that came out of a consultation with twenty-some individuals from the American philanthropic ecosystem. Taking the shape of a work seminar, they structured the discussions around questions on the role that operational and grantmaking philanthropy can play in:

- reducing the distance between citizens and American institutions;

- reinforcing citizen engagement or facilitating civic engagement è or again;

- giving the democratic ideal its second wind.

At the heart of the reported discussions, we find, formulated from a different angle, the big questions of the political crisis that is affecting the large institutions of American society.

The exchange was framed around the problem of divisiveness and whether there is a role for philanthropy in addressing the deepening cleavages in American society. Pluralism has always been a hallmark of the American experiment, but today there are growing concerns that our differences are tearing us apart. Many see the nation reverting to a kind of tribalism that not only threatens our social cohesion but also undermines key aspects of our democratic system. (London, p.2)

An important fact to note is that the ideological and cultural chasm that divides the American population also separates the stakeholders of its philanthropic ecosystem. Sherry Magill, of the Jessie Ball duPont Fund, sums up this reality well: “We’re not monolithic, we’re not all the same people, and we don’t all think alike.” The democratic ideal is under tension in the United-States. We are far from the situation described by Alexis de Tocqueville in the early 19th century.

What about Canada and its philanthropic ecosystem?

In her commentary published on February 14th, 2019 in the Globe and Mail, Lisa Kimmel, president and CEO of Edelman, the firm that publishes the Trust barometer, indicates that the deficit concerning the falling out of the democratic ideal is slowly approaching the situation already found in the United-States.

As Canada heads into a federal election, we are – more so than at any point in the past 20 years – a nation divided. The split is not East versus West, right versus left or English versus French. Today, it is a split between Canadians who fear the system is failing them and those who are more trusting of our traditional institutions and more optimistic about the future – for themselves and their families.

Kimmel ends her commentary with a call to CEOs of large Canadian companies to participate in the political sphere to rebuild trust and reestablish hope in the democratic ideal.

A lack of faith in the system has brought us to a tipping point. Walking us back from the edge demands a new approach to building trust and restoring hope. Leadership must come in new and different forms. Canadian CEOs, who have tended to play it safe, need to embrace this new reality and lead with a greater sense of purpose.

Lisa Kimmel’s call to action is based on the results of a survey of Canadians who claim that they trust their work environments to modify and improve their situation more than in the political system in place. Curiously, actors of civil society, including grantmaking and operational foundations, do not seem to be “the actors” capable of changing things. They are no longer the “go-to actors” that we could count on to correct the situation. Skepticism about the “System” gives the impression that all political stakeholders are included, implying that the leadership required to remedy the fallout can only come from the big market representatives!

The connection between philanthropy and democracy also appears to be a point of tension in Canada. To date, we do not have any studies, unlike the United States, that could shed light on the situation. However, I invite you to react to this editorial by expressing how you view the link between philanthropy and democracy. How do foundations in particular, and philanthropy, in general, have the capacity and legitimacy or not to join the movement that must be put into motion to restore faith in the democratic ideal?

Translation by Katherine Mac Donald

Would you like to send us your comments on the issue of democracy and philanthropy? Write to us at philab@uqam.ca, we would love to hear from you!

democracy and philanthropy democracy and philanthropy