The MasterCard enigma. This is how my colleague Sylvain Lefèvre, scientific coordinator of PhiLab, and I became curious about the intrigue that is the MasterCard Foundation (MCF), in both the field of modern philanthropy and of financial inclusion. For a philanthropy specialist, the MasterCard Foundation surprises because they find themselves almost outside the field, due to their size and speed of growth, without counting certain eccentricities which I will come back to further. For a financial inclusion specialist, this foundation is intriguing because their mission statements regarding inclusive capitalism appear to be the uninhibited outcome of an alliance between high finance and the world of international development, revealing the market’s interests concerning the initiatives at the bottom of the pyramid.

Out of this meeting of our political scientists’ curiosities emerged the ambition to dig around the terrain surrounding this foundation, with, evidently, a hint of researcher’s intuition in the background. We divided the work between us and I began examining the Foundation’s action plan, which is focused on financial inclusion in Africa, to observe the problematization of the opportunities for growth, for prosperity and for poverty as well as the financial tool trends supported by this philanthropic organization. I present here the paths and hypothesises that are emerging from by preliminary work. MasterCard seems to covet social revenues through their foundation by privileging access to financial markets for Africa’s vulnerable populations. This first glance indicates however that the MCF injects digital technologies, electronic money and programs of capacitation of excluded peoples who respond to the MasterCard’s firm’s business objectives into African agriculture. This suggests a blurring of borders, even a fusion, between the firm and the foundation. But first, here is some of the data from Sylvain Lefèvre’s analysis of this giant foundation.

A few characteristics of the MasterCard Foundation

By observing its structure, we can state that the MasterCard Foundation is, by far, the largest Canadian Foundation. With assets of nearly 10 billion dollars, they literally overflow from the field of modern philanthropy. Of the 10 500 foundations in Canada, only 56 have assets of over 100 million and only 6 have assets over 500 million[i]. With their 10 billion in assets, the MCF is extravagant, to say the least, in the landscape of the country’s philanthropy[ii].

The MCF’s mission aims “to advance education and financial inclusion to catalyze prosperity in developing nations”[iii]. It is led by a particular philosophy:

The MasterCard Foundation seeks a world where everyone has the opportunity to learn and prosper. All people, no matter their starting point in life, should have an equal chance to succeed. We believe that with access to education, financial services, and skills training, people can have that chance. Our focus is helping economically disadvantaged young people in Africa find opportunities to move themselves, their families and their communities out of poverty to a better life[1].

Financial inclusion and the MasterCard Foundation’s practices

Financial inclusion, which is at the heart of the Foundation, is an action plan put in place globally and has as an aspiration to include into formal finance, the entirety of the 2 billion and a half individuals that still have no access to what is considered to be a vital tool of development[iv]. Financial inclusion uses the method of microfinance services, including microcredit, meaning the attribution of small amounts to people who wouldn’t otherwise have access to these services. It is a project that aims at reinforcing access to and the utilization of formal financial services by marginalized populations, and this in a sustainable manner, thus a profitable one, which meets these populations’ needs.

After looking at the Foundation, and from my initial intuition, we must realize that financial inclusion has a double anchorage. On the one hand, it is an inclusive development tool feeding the big hopes at the heart of the international community who share a strong belief in the potential of emancipation and economic development resting on the access to credit and savings, for less-fortunate people and communities[v]. This anchorage is quite visible in the Foundation’s mission statement and philosophy. There is the emergence of real business around this phenomenon, as the financial industry and attached technology firms are searching for new niche markets to continue their rhythm of growth. The “bottom of the pyramid”, to once again take up the formula popularized by Prahalad[vi], is a promising territory for capitalist finance prospecting in the developing world.

The MasterCard firm is a financial technology company. It acts as a relay in transiting money between consumers, merchants, the States and the financial institutions who give credit, usually banks. Let’s imagine rails or conduits, properties of MasterCard, where electronic money transits between economic actors around the world. The product on the market offered by MasterCard, is not electronic money in the form of credit, it is the mode of transportation of the money, to which is joined all sorts of technologies to secure its transit. The more electronic money there is, the less hard cash is in circulation and the more business opportunities there are for MasterCard. The ideal world according to the firm is a society of digital economy, a cashless society.

This is paramount in understanding the firm’s interest in the financial inclusion project, which falls under a paradigm of development focused on technology to surpass obstacles and the spreading of access to formal finance to every corner of the planet. Electronic money is raised to the level of a flagship solution under this paradigm. It can be said that it is in MasterCard’s interests for financial inclusion to progress. Furthermore, they can position themselves at the interface with the States and mobile telephone operators in the distribution of funds from minimal social programs, as is the case in South Africa and Nigeria[vii].

The MasterCard Foundation Symposium on Financial Inclusion as a case study

To begin the exploration of the MasterCard Foundation’s practices in the domain of financial inclusion, I chose as a first destination the Symposium on Financial Inclusion (SoFI), held in Kigali in Rwanda in 2016. As it consisted in a ceremony of creation and knowledge sharing on invitation only, I found myself making this journey virtually, by exploring the information made public after the two days of the SoFI, those present, the presentations and debates that were held.

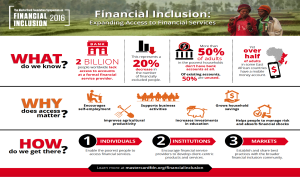

I first focused on the problematization of financial inclusion by the Foundation, which we can find in the logical framework provided and which is presented graphically in Figure1. The first thing which is exposed is the state of the problem, what we are supposed to know about financial exclusion (What do we know?). The MCF states a market gap: there are 2 billion people on the planet who are excluded from financial services. Next, they identify a progression, a hope in the capacity of capturing consumers: a recent 20% reduction in financial exclusion. We still see the gap, a global deficiency: with over 50% of poor adults not having a bank account and a significant under-utilization of existing accounts. Finally, a solution arises, a hope, a light at the end of the tunnel: the innovation of mobile bank accounts, which reaches more than a quarter of adults in East Africa.

The second series presented in this framework are justifications, the reasons that explain why financial inclusion is so important (Why does access matter?). The iconography is important in tracing the causal chain conjured by the MasterCard Foundation. According to them, financial inclusion would be beneficial to encourage independent work, would improve agricultural productivity, support business processes, increase investments in education and household savings, and help people manage risk and absorb financial shocks.

Figure 1: Logical Framework of the SoFI2016

Source: http://mastercardfdnsymposium.org/2016-symposium-report/

What we find here is basically the classic romance of microfinance. As Ann Miles, Director of the Financial Inclusion and Youth Livelihoods sector of the Foundation explains, “Ultimately, we worked at the Symposium to convey that financial inclusion is not an end in itself, but rather a vehicle to increase the economic resources and resiliency of the most disadvantaged, in turn leading to healthier and more prosperous families, communities and nations”[viii]. There is thus the proposal here of links between financial inclusion and the improvement of the quality of life of people living in disadvantaged communities[ix]. Finally, they propose a triad of solutions to reach it (How do we get there?) by associating individuals, financial institutions and markets. Notice here the absence of the State in the solution.

After having examined this logical framework, I wondered about the people who were invited to speak during this symposium. I noted the presence of different categories of experts who are patrons of key industries. Among these experts, we can find important names of the World Bank, the most renowned consulting institutions in microfinancing, experts in behavioural economy and in financial education, important members of the global community of impact investment and of the Development Fund for Development of the United Nations and representatives of African States. Among the business sectors present, the most shocking is the strong presence of mobile telecommunication companies and financial technologies.

An initial analysis of the themes covered by the speakers allowed me to identify the recurrent themes brought up at SoFi. Firstly, behavioural economy is put at the forefront. It would allow the entry into clients’ heads to mould their desire to use financial services, overcoming a barrier to inclusion. Professor Eldar Shafir, famous author of Scarcity: The New Science of Having Less and How it Defines Our Lives, expressed his support of the importance to “understand the behavioural aspects of client decision-making, and how financial service providers can use that information to better respond to what poor people want”. He then expressed during the symposium:

It is not enough to simply create a new financial tool. The process must be taken to the next logical step – raising awareness of the tool and how it can be used appropriately to improve people’s lives. … Client has to trust that the FSP has the customer’s best interests at heart; that the product or service will be beneficial in the long run; and that usage won’t cost more than any reasonable alternative.”

A second recurrent theme at SoFi in 2016 was that of financial technologies and in particular that of digital finance and mobile telecommunication. During a debate called Deploying Data to Understand Clients Better, the speakers brought up the initiatives “that benefit from behaviours to change the way clients think and act, in order to increase the use of financial services” and questioned “the role of the collection and analysis of data to reach these objectives”. They also discussed the “strategic partnerships that will help the providers of financial services to offer what the poor need, want and are expecting from them”.

From these two themes, we can question the distinction between the MasterCard firm and the Foundation. SoFi is a philanthropic event that essentially articulates itself around business strategies to increase financial inclusion which is simultaneously a global inclusive development project and a major business case for this payment technology firm. These are the first results of the preliminary analysis of the data from SoFi for 2016, which brings me to propose the hypothesis of a fusion of the firm’s business interests and the Foundation’s programs. The study of the data and that of previous and future SoFis will pursue in order to do a content analysis and to delve deeper into or study the Foundation’s structure (including its board of directors, its recipient organizations and partners) and observe in more detail the philanthropic programs of financial inclusion which are put in place on the African continent..

- Cobbett, E. (2015) “Making the international in contemporary South Africa: MasterCard’s Biometric Social Grant Card,” in Making Things International: Vol 1. Circulation, edited Mark Salter, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Roberts, Daniel. (2014). “How MasterCard Became a Tech Company”. Fortune http://fortune.com/2014/07/24/mastercard-tech-company/

- [1] Lefèvre, Agence du revenu du Canada, calculs: I. Khovrenkov

- [2]L’analyse de Sylvain Lefèvre (2017) a révélé d’autres traits particuliers de la FMC dans le paysage canadien : son champ d’activités tournées vers le développement international et une région du monde spécifique, l’Afrique; son lien fort avec les Nations Unies, dans le personnel et les programmes; et son articulation financière, thématique, mais non organisationnelle à l’entreprise MasterCard. Le conseil d’administration est en effet composé de notables du monde académique et des affaires, mais on n’y retrouve pas de représentant de l’entreprise MasterCard. On remarque également l’importance des dons faits aux universités et un accent mis sur la recherche et la formalisation des meilleures pratiques, couplé avec des programmes de fellowship imposants.”

To advance education and financial inclusion to catalyze prosperity in developing countries” - [3] http://www .mastercardfdn.org/about/

- [4] http://www.mastercardfdn.org/about/

- [5] Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Oudheusden, D. S. P. V. (2015). The Global Findex Database 2014. Measuring Financial Inclusion around the World. Washigton DC: World Bank.

- [6] GPFI. (2016). Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion: Work Plan 2017. Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, G20. UNCDF. (2014). La finance inclusive pour une croissance inclusive. United Nations Capital Development Fund. World Bank. (2008). Finance for All? Policies and Pitfalls in Expanding Access. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (2014). Global Financial Development Report: Financial Inclusion. Washington, DC: World Bank. - [7] Prahalad, C. K. (2004). The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson.

- [8] Cobbett, Elizabeth. 2017. “High Finance, Material Life & Fintech infrastructures: MasterCard in Africa”. Working Paper.

- [9] “Ultimately, we worked at the Symposium to convey that financial inclusion is not an end in itself, but rather a vehicle to increase the economic resources and resiliency of the most disadvantaged, in turn leading to healthier and more prosperous families, communities and nations”. Milles, A. 2016. “‘Inclusion is Not an End in Itself’: Takeaways from MasterCard Foundation’s Symposium on Financial Inclusion”. NextBillion Blog.

- [10] Je n’ai pas l’espace pour traiter ce débat sur les impacts des microcrédits sur les clientèles, mais je soulignerai que des cas de surendettement liés à la distribution massive de microcrédits au niveau des communautés, des individus, comme des pays, se multiplient avec la tendance à la commercialisation du secteur, portant aux nues les risques inhérents à ce qui prend de plus en plus la forme de subprimes du Sud Global. Voir entre autres: Fouillet, C., Guérin, I., Morvant-Roux, S., & Servet, J.-M. (2015). De gré ou de force: le microcrédit comme dispositif néolibéral. Revue Tiers Monde(225), 21-48; Guérin, I., Morvant- Roux, S., & Villarreal, M. (Eds.). (2014). Microfinance, Debt and Over-Indebtedness: Juggling with Money. London: Routledge.; Lagneau-Ymonet, P., & Mader, P. (2013). Du microcrédit aux « subprime » pour les pauvres. Le Monde diplomatique (28 septembre).

- [11] “understand the behavioural aspects of client decision-making, and how financial service providers can use that information to better respond to what poor people want”