Michael Howie is the Director of Communications and Advocacy at The Fur-Bearers, a charitable organization that advocates on behalf of fur-bearing animals in the wild and in confinement. Michael began his career in journalism and earned more than a dozen awards for reporting on crime, the environment, editorial writing and news design, prior to moving to the non-profit sector. In addition to writing and strategic communication duties, Michael hosts and producers Defender Radio and The Switch podcasts, available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and at DefenderRadio.com. He can be followed on Twitter @DefenderRadio, Instagram @Howiemichael, and Facebook at the Defender Radio Podcast page.

Interview by Katherine Mac Donald

Katherine Mac Donald (KM): Could you begin with a brief introduction of your role at The Fur-Bearers, as well as a brief overview of what the organization has been working on recently?

Michael Howie (MH): I’m the Director of Communications at The Fur-Bearers. I joined in 2014, with a background in journalism. I worked in traditional media for over 10 years, won about 17 awards, mostly focused on crime, environment, and politics, before transitioning into advocacy work. My role at The Fur-Bearers is very much content related, such as our weekly podcast and blogs on educational issues. We often respond to news and commentary and provide alternative perspectives, as well as create content campaign work such as door hangers regarding the presence of bears [in communities]. The Fur-Bearers is a charitable organization founded in 1953 to advocate on behalf of fur-bearing animals in the wild and in confinement. A fur-bearing animal is defined as an animal whose pelt has commercial value. There are more than a dozen in Canada, ranging from squirrels up to grizzly bears. A lot of our work has to do with trapping and fur farming. Trapping is everything from letting folks know it is happening so they can take safety precautions, to trying to get very common-sense changes like warning signs and clearly understood rules about where traps can go. The goal is to eliminate this very specific activity that is causing a great deal of suffering. Fur farms became more of an issue in the last year, as mink and other animals farmed for their fur are potential vector points for COVID-19 and other viruses, making them a danger to public health.

Our other main campaign is coexistence with wildlife. Why is there often a call for trapping and a need for lethal wildlife management of fur bearers? In many cases it is because people are unable, unwilling, or unknowing of solutions that exist. If you don’t know that there are companies who specialize in humanely removing wildlife from your home and sealing it up behind them, you are not going to seek that out. Instead, the seemingly straightforward solution of trapping is sought out (with the term “humane” being used frequently, though it is never defined) with a tragic outcome for either the animals in question or others. Coexistence has become a staple of what we do, and we focus heavily on solutions, helping municipalities and communities identify and utilize those resources.

KM: Is there any definition that is used for what is considered humane regarding trapping of fur-bearing animals?

MH: There is a trade agreement to which Canada is a signatory called the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards that was signed in 1997. It purported to create a system that would ensure the most humane traps would be used, largely in response to international pressure to stop using leg-hold traps, which remain legal in this document. The document itself sets out scoring data for the type of injuries that can occur and what is a pass or a fail. But they never actually define the word humane anywhere in the agreement. You’ll hear people talk about humane certified traps, but what that means is that it falls under the auspices of this agreement. It doesn’t mean it is more or less humane than anything else. That’s how we end up with people asking for a humane trap and expecting a cage trap, and instead get a cuff trap for raccoons which leaves devastating injuries. You can’t get anyone to agree on what humane means because it’s not tangible, it is an idea that you strive for.

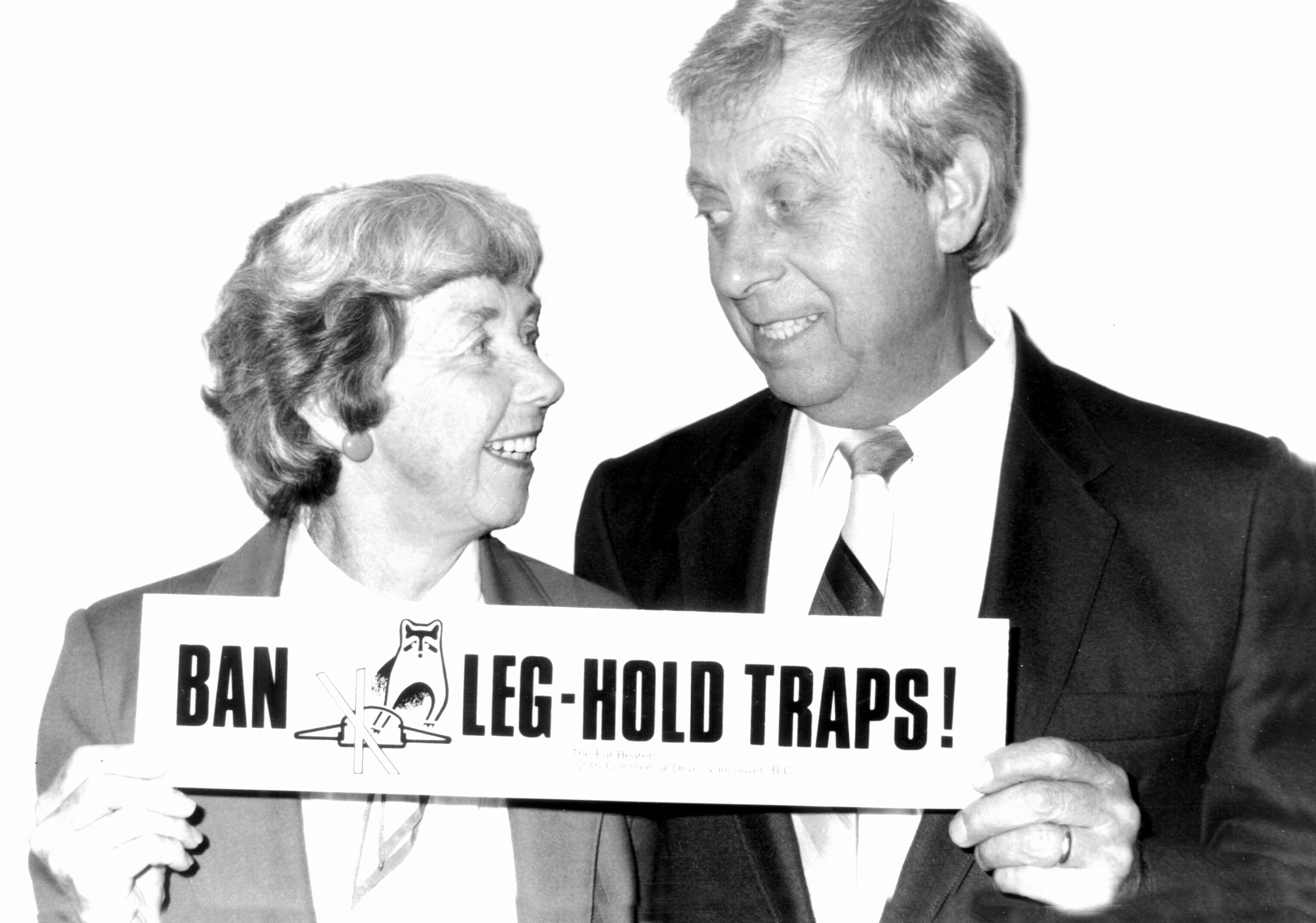

KM: There was a shift in strategy in the seventies away from promoting humane traps towards banning fur as an industry. How would you explain that shift and the impact it had on the organization’s strategy?

Photo Credit: The Fur-Bearers

MH: The idea of The Fur-Bearers started in the 1930s before WWII via editorial letters in newspapers, with people saying there had to be a better way to get a fur coat than using these traps. Different approaches were considered including mink farming. The thought was: can we ranch these animals in a way that will be more effective, more humane? There were many trap developments, and the early group of The Fur-Bearers contributed funding to what would become known as the Conibear Trap because it was believed to be a quick kill trap at the time. Of course, we now know that that quick kill trap can be set off by any animal, that it won’t always land correctly, and that it won’t always kill quickly. It was these situations that led to the realization that there just isn’t a good way to do this. That really led to the change in how we moved forward.

When you consider the perspective that we want to catch an animal against their will, kill them and skin them, is there really a humane way we can do this? As we noted about the term humane, it becomes very relative. At this point, there is no need for fur for the general public, and no need to be going out killing and injuring all these animals. Our goal then became getting rid of the leg-hold trap and reducing trapping efforts overall.

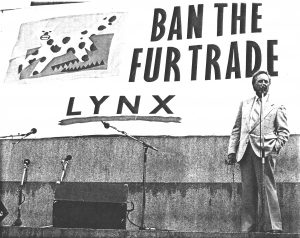

KM: Advocacy, be it environment, animal, or human-centered, is a big issue in the charitable sector. The Fur-Bearers had their charitable status revoked in 1999. Was there anything specific that triggered this? How did it affect your fundraising capacities, and did it lead to any other challenges?

Photo Credit: The Fur-Bearers

MH: I’m sure there are more specific documents that discuss this situation, but some 22 years ago, the Canada Revenue Agency said: “You are advocating against a legal and regulated industry in Canada. That is not a charitable activity, and you should not be doing it.” Unlike other groups who had received the same message, we did not back down. There is a video of George Clements, one of our longtime directors discussing if charitable status was more important than the work we were doing. The truth is it wasn’t. The feeling was that these things have to be said, they have to be shown, and we would find a way forward. That said, we lost roughly 50% of revenue when we could no longer issue tax receipts. One of the biggest impacts that we have felt in addition to the tax receipts is our inability to apply for most grants. Because we couldn’t get grant funding to launch programs, we had to find very grassroots ways to accomplish something that other groups would expect $25 000 to $50 000 in grants to do so. We had to rely on people who were willing to give us $5 to $10 because they believed in the cause.

KM: In 2020, The Fur-Bearers got their charitable status reinstated. How did this impact the organization’s capacities?

MH: With our charitable status reinstated, we’re very excited about grants. Our entire strategic planning process is different as a result of that alone. Now that we can actively apply for grants, the pressure is off individuals and we can fund programs separately. It just opens the doors in terms of options and how we want to move forward.

I still remember when we got the notice, it was December 2020, the day after our newsletter for supporters went to print. I got to call the printer and say, stop the presses! Rather than scrap a bunch of newsletters, we wrote a letter and added it to the front to announce we got charitable status.

KM: Have you seen an increase in donations since?

MH: So, it’s only been a year and two months and our first full fiscal year has not yet closed. Without going into specifics, I’d say our average donation amount has gone up and we are seeing different donors. We have also already successfully applied for a handful of grants that we previously would not have been able to and as such have done work in communities to support wildlife. When there’s funding options on the table, planning the work that needs to be done becomes a very different conversation.

KM: Donations towards animals are often lumped in with environmental causes, which together still amount to a very small percentage of total donations. What obstacles could help explain why such a small percentage of people are donating to these causes?

MH: For one, it is a lot harder to make it personal. I genuinely think that is the largest roadblock. It is very easy to speak with empathy to someone about children or seniors anywhere in the world because we all have connections with them. I think when we talk about human-focused charities, we can see ourselves or our families in them, and empathy is so much quicker to connect. If you put polar bears on an iceberg in front of me, I can’t personally connect to that as easily. I think as an empathetic animal lover, I can, but as a standard human being, there is a disconnect. We can call it speciesism, or we can call it bias, but there is this sense of: that’s not me. It is harder to get to the empathy which leads to action. One of our challenges is reminding people that trapping even exists. Every year I speak to people whose beloved pets have died in traps, and the first thing they say is they had no idea traps existed because it’s just not talked about.

Photo Credit: The Fur-Bearers

The Fur-Bearers annual Christmas Tree Fundraiser

KM: Wouldn’t the fact that pets get caught in traps be a way to make protecting wildlife more personal, as many people have a connection to pets?

MH: Yes, but it also becomes problematic. A wolf can experience grief and joy, and I can tell you the story of a wolf experiencing those things. But for me to say that this particular wolf is going to do better because you’re donating is where the disconnect arises. I’m talking about wolves or beavers as a species across the country, not individuals. For example, we’ve had programs that put in-field solutions for beavers, and those can be hard to talk about because not everyone knows beavers. They don’t know that they are a family-oriented species who live in multigenerational homes, have the greatest impact on the environment other than humans planet-wide, and can create clean surface water and save us from droughts. Before I can try and make an emotional connection to beavers, I also have to give all of this information, which requires the potential donor to listen for two minutes.

That is the other element of the problem. How do I get an audience to stick with me so I can set up all of this information about why it matters? In contrast, wildlife rehabilitation charities can show you the specific animals they’re rehabilitating and releasing. Our work is sometimes sitting in a room with a bureaucrat for two days, hammering out the language on a policy. That’s just not appealing to a donor, even though it might have a significant impact on many animals. It’s just so much harder to draw that picture, tell that story, create empathy and walk someone down the path towards a donation so that we can do the work.

Another problem we can associate with building a personal connection to attract donors can be seen in how megafauna clearly get more funding. When you look at the science of the animal kingdom, that’s not where the funding should be at all. It should be on the insects, the small animals and the habitat’s biodiversity. It is very easy to simplify, but then you’re not necessarily telling the true story, which brings its own downfalls.

KM: Do you feel this is where grantmaking philanthropy can fill a gap since they already have a specific mission that they are looking to fund? They might be more likely to understand the issue on a more systemic level?

MH: With granting, we can take the expected or desired outcomes of a campaign and go to a grantor and say effectively: if you’re interested in this kind of outcome, here are the three steps we’re going to take, why we need your money to do it and what you can measure it against. Say we want to train five people through the Beaver Institute to help resolve human-beaver conflicts using non-lethal and scientifically-proven techniques. That means we’re going to need $1500 per person for the scholarship, X amount of time, and Y amount of additional funds for support. That’s a difficult pitch to the general public because the outcome is very abstract: I can’t show you the beaver who’s going to be saved. All I can tell you is our capacity to reduce the need for trapping will be increased significantly, which is the objective. In terms of how grants can help, it is by funding these very specific programs that need to happen, but just do not sound as exciting to donors.

I also feel this relates to the general complexities of doing charitable work and the difficulties in funding internal capacity. I grew up in a very conservative household and heard a lot about charities growing up and how only 80 or 60 cents on the dollar actually goes to this or to that. But then, how did you get these numbers? It’s because someone was there counting the pennies to be able to tell you. That’s why they need you to donate; because someone has to count the pennies, so they actually get used. Someone has to be there to also deliver the program. I know if we want to do anything, we need people. If we want people, we need to give them resources and resources cost money. That’s the bottom line of it all. It’s like any business, if you want growth, you must invest.

KM: With the sometimes very demanding impact reporting expected with grants, as well as from donors, what are the unique challenges animal organizations face regarding impact measurement?

Measuring impact is always difficult, and I think it becomes even more so when you can’t ask the person who benefited a qualitative question. One of the best choices I’ve ever made in my life was being a mentor with Big Brothers, Big Sisters. They send out promotional material sharing a youth’s mentoring experience, and how now they’re a lawyer. That’s pretty compelling in terms of fundraising language. Well, we can’t ask the squirrel: How do you feel now that peanuts aren’t being offered to you, causing you to get too fat, stop eating local food, allowing invasive plant species to take over, creating an unbalanced ecosystem? It makes the impact reporting more abstract, and less compelling, but I don’t want to make up stories, I want to tell true stories and we do. That can be much more difficult for fundraising. I could make someone weep in two minutes of writing, but it’s not going to be the truth, and that matters more. It matters more that the true stories get told.

Source: https://thefurbearers.com/blog/wildlife-in-the-attic-who-ya-gonna-call/ Photo Credit: Bubblegirlphoto / Getty Images

KM: Do you have any hopes for the future of animal-related philanthropy?

MH: I think something we are going to see more of is tagging animals and environments to people. This is also the reality of the situation, a lot of what’s happening to our environment and to animals is a result of humanity, it is all interconnected. I think it will become more of a straight line between a funding proposal or need that serves animals, and funding from individual donors and grantmaking foundations.

KM: Thank you very much for your time and all the important work you are doing advocating for fur-bearing animals Michael.

This article is part of the special edition of January 2022 : Philanthropy for the Animals. You can find more information here