Climate change is affecting weather patterns around the world. Natural disasters are now more frequent and more intense. And the increased impact of climate-linked natural disasters is already transforming the role of emergency management in Canadian society. As more and more people are displaced by natural disasters – more often, for longer – the demand for emergency social services has ballooned. That, in turn, has prompted the dramatic transformation of Canada’s leading emergency management nonprofit, the Canadian Red Cross.

Climate change is affecting weather patterns around the world. Natural disasters are now more frequent and more intense. And the increased impact of climate-linked natural disasters is already transforming the role of emergency management in Canadian society. As more and more people are displaced by natural disasters – more often, for longer – the demand for emergency social services has ballooned. That, in turn, has prompted the dramatic transformation of Canada’s leading emergency management nonprofit, the Canadian Red Cross.

This blog post tells the story of the Canadian Red Cross’ transformation from 2013-2019. It is based on an in-depth case study included in my Ph.D. dissertation (which you can read here for more detail, including a description of the methodology). The Red Cross’ role in emergency management grew initially through philanthropic contributions, but it has since become institutionalized as a part of the Canadian welfare state. This story raises questions about the relationship between philanthropy and government.

Canadian Climate-linked Disasters

Canada’s climate disaster era probably started in the late 1990s. Senior Climatologist David Phillips (2019) suggests that it began with the 1996 flood in Saguenay, Quebec. But in the last decade – and especially since 2013 – the acceleration of climate-linked disasters has become a clear, unignorable trend.

2013 is an important date because it is the year when one of Canada’s costliest and most devastating disasters occurred. In June 2013, Alberta’s Southern Saskatchewan River Basin flooded, precipitating over 30 local states of emergency, four deaths, and the evacuation of 125,000 people (Mackwani 2015). Close to 15,000 homes were flooded, about a third of which sustained major damage (Mackwani 2015). The financial impact of the disaster was without precedent in Canada: in total, the flooding caused $7 billion in losses, comprising $5 billion economic losses and $2 billion insured losses (Mackwani 2015). The impact of this disaster is still being felt.

Three years later, in 2016, a warm spring brought an early wildfire season to Northern Alberta, necessitating the evacuation of communities in the Wood Buffalo Region. 88,000 residents were evacuated. Many Canadians will remember images of cars fleeing walls of fire on Highway 63, the only road out of Fort McMurray. The Northern Alberta Wildfires constituted the costliest natural disaster in Canadian history, with a total estimated economic impact of $8.9 billion.

There is now a well-established pattern of concurrent natural disasters in Canada. 2017 and 2018 made fewer headlines, but they were record-setting wildfire seasons – and years with significant flooding across numerous provinces. The 2018 British Columbian wildfires, which affected every region of the province, also caused record-breaking air pollution levels in Alberta (CBC News 8 January 2019). Overall, Canada was the ninth most disaster-affected country in the world

in 2018 (Eckstein et al. 2019). In 2019, “hundred-year” or otherwise major floods affected multiple provinces – this time Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick – and an “extreme” wildfire season occurred in the west – this time in Alberta. As climate change accelerates, emergency management professionals are confronting a new reality of concurrent natural disasters happening over increasingly long durations, and with cumulative effects.

Climate Disasters and the Nonprofitization of Emergency Management

Climate-linked disasters in 2013-2019 have prompted changes to the landscape of emergency management. This case study focuses on the transformation of the Canadian Red Cross. The Red Cross has agreements with local, regional, provincial, and federal governments across the country – over 800 at the local level alone. Today, it is involved in every major natural disaster in Canada, frequently taking on a lead role in supplying emergency social services – and usually with the understanding that government will reimburse direct costs.

This was not always the case: until the climate era emergency management was a small program area. Prior to 2013, the Red Cross was primarily focused on international operations, water safety, and health programs. From 2004-2015, emergency management comprised an average eleven percent of the organization’s budget (Sauvé 2019). Emergency management is today the single largest program area, making up 50 percent of the budget (Sauvé 2019). As the Red Cross looks ahead to its future, the society sees emergency management as a service with further growth potential: “We are confronted by a growing reality and now we need to change to meet that scale” (Sauvé 2019).

When the 2013 Southern Alberta floods occurred, the Red Cross raised a staggering $45 million dollars in its largest ever domestic disaster appeal. Because the disaster appeal was so large, the Red Cross had the resources to move beyond immediate assistance in the response phase of the disaster. It was able to support individuals in long-term recovery, aid community groups to return to operating capacity, and fund resilience-building projects. Through its Community Grants Program, CRC funded 70 projects in affected communities. The Southern Alberta floods were the Red Cross’ first experience as a grant-maker – a transition that was not always been smooth.

Although the disaster appeal was an important enabling factor, the Red Cross’ expertise made the transformational effect of 2013 possible. In addition to its direct experience with Canadian emergency management, the Red Cross, had expertise in the related fields of health, first aid, and international disaster assistance.

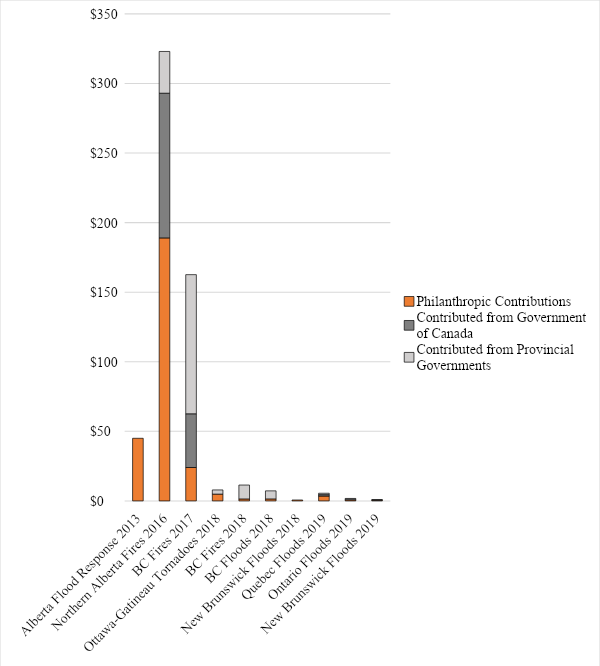

The 2016 Northern Alberta wildfires again stretched the bounds of the Red Cross’ emergency management capacity, in particular because of the unprecedented resources at their disposal for this event. The 2016 Alberta Fires appeal raised a total of $323 million from a combination of philanthropic and government sources. While disaster appeals have slowly dwindled since 2017, the Red Cross continues to be an indispensable government partner in major disaster events. The chart below provides data on Canadian domestic disaster appeals opened by the Red Cross in 2013-2019. The 2016 Northern Alberta Wildfire appeal is noticeably larger than other disaster appeals, both in terms of philanthropic and government contributions. The 2017 British Columbian wildfires appeal was about half as large – and largely comprised of government

funding. In 2018 and 2019 a series of concurrent disasters drew small disaster appeals. While there were fewer evacuees in the disasters of 2018 and 2019, their cumulative effect has been considerable.

Chart. Canadian Red Cross Domestic Disaster Appeals 2013-2019

Climate-linked disasters have expanded disaster assistance budgets, prompted policy reviews, and increased the role of emergency management nonprofits. They have also led to the ad hoc creation of new forms of assistance: government donation-matching and its offshoots, as well as the use of cash transfers during early disaster response. Both of these new practices have further expanded the role of nonprofits, especially the Red Cross.

During the 2016 Northern Alberta wildfires both the Government of Alberta and Government of Canada pledged to match citizens’ donations to the Red Cross. Spending on donation-matching was not trivial: the Government of Canada contributed $104 million in matched donations, while the Government of Alberta contributed $30 million. The decision to match philanthropic donations in effect brought voluntary sector policy into emergency management. Government could have (and also did) decided to directly fund nonprofits, to fund governments above financial assistance program levels, or to provide direct funding to individuals. By opting to match philanthropic donations to a particular nonprofit, the intention was to encourage individual Canadians to get involved and to match public investment with public interest in the event. 2016 marked the first time that the Canadian government had ever pledged to match donations for a domestic disaster appeal.

Matching philanthropic donations has not become expected practice in Canadian emergency management. The federal government faced questions about whether it would match donations to the Red Cross at the onset of the 2017 British Columbian wildfires, but ultimately it decided to contribute funds without the donation-matching component. The Province of British Columbia did match Red Cross donations up to $20 million in the 2018 British Columbian wildfires, but this has not proven to be the norm.

Nonetheless, the 2016 Northern Alberta wildfire has generated an expected practice of funding Red Cross disaster response and recovery. Out of the nine events for which the Red Cross has opened a domestic disaster appeal since 2016, Canadian governments have contributed funds to eight. Government contributions have been, on average, 53 percent of the total disaster appeal. Governments also contribute to the Red Cross for smaller scale disasters, especially where such disasters frequently recur. For instance, the Red Cross has a contract with Indigenous Services Canada in Manitoba for the cost of carrying out emergency management for First Nations disasters in the province.

Philanthropy has proven to be unreliable as a source of disaster funding in the climate change era, where fires and floods happen regularly and simultaneously – making it more difficult for individual events to capture public attention and sympathy. While philanthropic disaster appeals enable nonprofits to do an immense amount of good, philanthropy can be fickle and arbitrary: the result is that resources may not match the need, and as such care can be unequal from event to event. Certainly, the Northern Alberta wildfires affected a large group of people, some quite acutely. But on a per evacuee basis, the 2016 Northern Alberta wildfires raised four times as much philanthropic funding as the 2019 Spring Floods in Quebec, Ontario, and New Brunswick: $2,148 was raised per evacuee in the former disaster, compared with $527 for the latter.

And this ignores the medium-scale natural disasters which seldom draw sufficient interest to open a disaster appeal. Annual evacuations of First Nations communities, for instance from Kaschechewan and Kapuskasing, are among this subset of disasters that are largely ignored by philanthropy. Generally, the chart above depicts the rapid dissipation of philanthropic interest in Canadian disasters: since the 2016 Northern Alberta wildfire, eight disaster appeals have raised a combined total of $37 million in philanthropic contributions – $24 million of which was from the 2017 British Columbian wildfires.

As philanthropy has dried up, the Red Cross has turned to governments to fund disaster response. Federal and provincial governments have provided between 38 percent and 88 percent of Red Cross disaster appeal funding in 2016-2019. The nature of the Red Cross’ work has changed from a periodic mobilization of resources on an as-needed basis to a practice of being permanently deployed. Both because disasters are more frequent and because the society is engaged for longer, Red Cross personnel are now constantly engaged in dozens of active incidents. As resources become increasingly strained, the Red Cross is reaching out to governments across the country for stable base funding for capacity, such as the cost of keeping equipment in warehouses.

In the climate change era, the practice of emergency management increasingly relies on upfront government funding to the Red Cross, which provides direct assistance as well as cash transfers for evacuees. The details of assistance are determined by the relevant governments. In addition to provincial and federal government funding for Red Cross disaster appeals, the Red Cross and other nonprofits frequently receive reimbursement for providing direct disaster assistance to Canadians. Especially during large disasters, nonprofits can typically recover costs for direct costs of service delivery. The reason that cost recovery is more common in major disasters is that these open up disaster financial assistance programs at higher levels of government – so, municipalities bill the province, who then bills the federal government under the Disaster Financial Assistance Agreements program. In rarer cases, agreements with government agencies also include a financial contribution for capacity-buildings.

The 2013 Southern Alberta floods and 2016 Northern Alberta wildfires were both transformative for the Red Cross’ role in disaster response, in large part due to the massive philanthropic resources at their disposal. In 2017 and onwards, philanthropy has been a smaller presence, but the Red Cross role has not diminished: instead, the society is deepening its integration in the welfare state. Whether this consists of administering government cash transfer programs for immediate emergency assistance or providing direct assistance in accordance with government guidelines and on the expectation of reimbursement, it is clear that the Red Cross’ role in Canadian emergency management increasingly looks like the government acquisition of social welfare services.

Conclusion

Today, Canadian emergency management policy guards against social risks posed by climate-linked disasters. While these risks are not new – natural disasters have, of course, occurred throughout history – the frequency and scale of disasters has moved emergency management from the fringes to occupy a larger role within the welfare state. There is a growing sensibility that climate-linked disasters are not merely “natural” events and are not randomly distributed. Rather, there is an emerging sentiment within the profession that climate change is putting certain communities at greater risk and these risks need to be addressed through social policy.

While the basic policy architecture of emergency management has, for the moment, remained – governments provide direct assistance and offer financial aid during very large events – catastrophes in the climate change era have strained these policy structures and prompted the use of additional interventions, especially cash transfers. Emergency management has also nonprofitized to a greater degree, with the Canadian Red Cross taking on an omnipresent role within the span of a decade. For the moment, the boundaries of individual versus collective responsibility for private wellbeing is shifting on an episodic basis. But as disaster assistance becomes a new pillar of the welfare state in the climate change era, this is starting to change.

In the Canadian context, the climate change era has expanded the role of the Red Cross and deepened its interconnections with governments at all levels. Climate disasters, especially in 2013 and 2016, have extended the length and nature of the Red Cross’ involvement in disasters, rendering them ubiquitous Canadian emergency management actors.

Philanthropy led this shift through the exceptionally high contributions to domestic disaster appeals for the 2013 Southern Alberta floods and 2016 Northern Alberta wildfires. The impressive scale of disaster appeals in these cases points to the important role that philanthropy can play in defining new social risks. Yet experiences in 2017-2019 have also illustrated the limitations of philanthropy. As concurrent disasters have split the public’s attention – resulting in lackluster philanthropic support for disaster appeals – the Red Cross is increasingly looking to government to provide stable, equitable disaster response and recovery funding. As this process continues to unfold, it remains to be seen whether government will continue a policy of funding nonprofit emergency management, rather than taking over assistance or bringing the Red Cross officially into government. Already it is clear that the Red Cross sees itself, and is seen, as a member of a “club of governments”.

Unfortunately, the climate crisis has barely begun. Recent global disasters such as the Australian bushfires, Cyclones Idai and Fani, floods in the Iranian province of Khuzestan, Hurricanes Florence and Michael, and the Californian Camp wildfires, have alerted the world to the potential scale of climate-linked disasters both for ecosystems and human communities. Canada’s experience in 2013-2019 is revealing a typical pattern for this country’s disasters in the climate era: ice storms on the eastern half of the continent, coastal flooding, heatwaves, wildfires in western Canadian forests, and inland flooding, all happening concurrently.

But as the scale and frequency of these events intensifies, the strain on existing policy will necessitate a response beyond the ad hoc approach taken to-date. Or more accurately, given the tiered doctrine of emergency management in Canada, responses. Will Canada adopt an approach more akin to the British system of mandatory private insurance? Possibly, but the prominence of flooding in the British case leaves some uncertainty about how well this would work in Canada. Will it seek to create its own version of the American Federal Emergency Management Agency? It is difficult to imagine given the sensitivity of provinces and territories to federal takeover of shared responsibility. An additional possibility draws on roots already established in 2013-2019: the intergovernmental use of a nonprofit, the Red Cross, to bypass constitutional sensitivities. The nonprofitization of emergency management may prove an enduring Canadian approach to the climate crisis.

This article is part of our Special Edition: Philanthropy, Climate Change & the Environment.