This article touches upon corporate philanthropy, independent of corporate social responsibility (CSR). We see it as an action domain that allows companies to gain credibility in the eyes of their stakeholders. The current text sheds light on the concepts of corporate philanthropy, which refers to the voluntary contribution of private corporate resources towards public interest objectives (Gautier & Pache, 2015). According to the statistics of organizations such as Charity Navigator, in the United States, corporate donations increased by 8% in 2017 and represented 20.77 billion American dollars (Charity Navigator, 2019).

In this situation and despite the abundance of scientific literature on the CSR construct, the place and role of corporate philanthropy, compared to that of CSR, is still the object of controversy. In recent literature, corporate philanthropy has often been considered as an outdated, traditional and simplistic dimension of CSR (Volpentesta, 2016; Liket & Simaens, 2015).

We thus present an exploratory literature review that demonstrates how today, corporate philanthropy is a complex phenomenon that can rid itself of the CSR label. Also, we propose a specific angle to qualify corporate philanthropy and we will do so by resorting to the theory of legitimacy.

Corporate philanthropy: altruism or profit-seeking behaviour?

The concept of philanthropy finds its roots in ancient Greek. The term philanthropy stems from the word philos (friend and/or loved one) and anthrôpes (Man or humankind). In fact, the concept is often defined as “love of humankind” (Volpentesta, 2016). According to Sulek (2010), the actual meaning of the concept has evolved throughout history, Today, it is more based on the promotion and advocacy of social well-being. Corporate philanthropy originated at the end of the 19th century and the phenomenon mostly developed throughout the 20th century. This period was marked by the strong growth of the capitalist system, which favoured companies resorting to philanthropy to respond to community needs (Carroll, 2008).

On a conceptual level, corporate philanthropy conjures an oxymoron, as the donation of monetary or in-kind resources contradicts the company’s for-profit goal. According to Fenclova and Coles (2011) and Gautier and Pache (2015), the definitions given in the scientific literature can be placed on a continuum where altruism and profit are positioned at the extremities (see Figure 1). In general, corporate philanthropy practices can take on three main forms: corporate charity (monetary or in-kind donations), corporate volunteering (by the company’s employees) and corporate foundations (charitable foundations that are funded by a private company), (Honey, 2011).

Figure 1 : Adaptation of the definition of CP by Gautier and Pache (2015).

Since the 1990s, the highly competitive context of the business world has accelerated the consideration of the many impacts of corporate philanthropy as well as its use as a strategic tool (Carroll, 2008). Gradually, this new trend appeared within companies as their leaders understood how they could benefit from their own philanthropic actions. This thought-process gave way to an instrumental approach to corporate philanthropy: strategic philanthropy. According to several authors, Porter and Kramer for example (2002), Carroll, (2008) and Waddock, (2008), this approach is distinguished by the alinement of corporate philanthropy initiatives with the company’s objectives, mission, and values. This allowed companies to touch on social problems and improve their strategic position (Novelli et al. 2016). In this way, strategic philanthropy is presented as a managerial practice that is able to fulfill the company’s own objectives as well as society’s social, environmental and economic objectives (Porter & Kramer, 2002). However, is it really possible to combine society’s interests with those of private companies through corporate philanthropy? In order to answer this question, studies have delved into the motivations and impacts of corporate philanthropy.

From the company’s point of view, on the one hand, corporate philanthropy has the capacity of creating positive impacts for them, as well as their stakeholders. More precisely, it helps foster a positive attitude, among consumers, that increases their visibility, improves their reputation and image and thus, their sales (Fenclova & Coles, 2011; Gautier & Pache, 2015). Also, philanthropic actions help reinforce employee productivity and stakeholder loyalty (Carroll, 2008). According to Godfrey (2005), corporate philanthropy helps build positive moral capital, which increases the value for shareholders. On the other hand, critics argue that corporate philanthropy mainly acts as a way for companies to polish their image. Companies want to be seen as being environmentally and socially responsible whereas they aren’t necessarily (Waddock, 2008). According to this point of view, stakeholders might be skeptical regarding a company’s philanthropic practices.

From society’s point of view, the strategic aspect of corporate philanthropy allows for the establishment of close relationships based on trust between companies and concerned stakeholders by responding to their expectations and needs (Wang et al., 2018; Weeden, 2015). In addition, corporate philanthropy could represent an efficient tool in developing a more responsible managerial approach in order to contribute to the well-being of society (Goodwin et al., 2012).

Corporate philanthropy as a CSR practice

Establishing a consensual definition for the concept of CSR has been difficult within the scientific literature. This is caused by the multifaceted use of the concept that covers a vast collection of differentiated subjects in management. In general, the concept of CSR is the result of a thought exercise on the nature of companies, their social role and the relationship between their stakeholders and society (Volpentesta, 2016). More specifically, CSR refers to a management philosophy that considers that private companies have an array of social responsibilities towards stakeholders other than shareholders and investors. Regarding corporate philanthropy, scientific literature has intricately connected the two concepts. In fact, they share a similar nature and origin, which caused the two to be interpreted as identical concepts, especially during the early years of CSR’s development (Wang et al., 2018; Porter & Kramer, 2002 è Volpentesta, 2016). The ambiguous relationship between the concepts of CSR and corporate philanthropy has been mainly covered from these two points of view.

Corporate philanthropy is primarily considered as a key element, or sub-dimension of CSR (Carroll, 1991; Godfrey, 2005; Waddock, 2008). Under this perspective, Carroll (1991) differentiates four steps or components of CSR:

- the required economic responsibilities;

- the legal responsibilities to which companies must conform;

- the ethical responsibilities that are expected; and,

- the philanthropic responsibilities that are desired by society.

While these studies have greatly contributed to the founding of a disciplinary field of CSR, they have perhaps limited the development of the corporate philanthropy concept. For example, recently, Alvarado-Herrera et al. (2017) created a scale of consumer perception of CSR by using a three-dimensional conceptual approach: social, environmental and economic. The scale includes several aspects related to corporate responsibility, but the phenomenon is hardly distinguished from other concepts, such as sustainable development.

Along the same lines, according to Varadarajan and Menon (1998), corporate philanthropy is a CSR practice that can be considered a marketing strategy. This study is relevant from a managerial perspective but shows a reductionist vision of the phenomenon. In fact, the authors have not taken into consideration other stakeholders (such as consumers and recipients of philanthropic aid) who also play an important role in the comprehension of the concept. Finally, according to Zheng et al., (2015), today, CSR operates from two main practices: corporate philanthropy (related to the social and community involvement aspects) and the environmental impact of projects (related to sustainable development and environmental aspects). Zheng et al.’s study (2015) proposes an easy categorization of CSR practices but oversimplifies the concept of corporate philanthropy.

Paradoxically, the arguments used to explain corporate philanthropy’s inclusion in CSR are, in large part, the same arguments that push for it to be seen as a concept exclusive to CSR. First of all, the increase in environmental consciousness has caused companies and scientific literature to associate CSR more and more with the concept of sustainable development (Jain & Winner, 2016; Moon, 2007 & Visser, 2008). Second of all, according to von Schnurbein et al. (2015) and Leisinger (2008), the voluntary and discretionary character of corporate philanthropy would give this managerial approach its own conceptual identity. Thus, CSR would be strongly connected to the company’s fundamental activities and the organization would only implement philanthropic activities once the required responsibilities (economic and legal) and expected responsibilities (ethical) were fulfilled. We would defend the position that corporate philanthropy is a complex phenomenon that is at the heart of the crossroads of business and society and is made up of a series of not only economic dimensions but also cultural, social and political ones amongst others.

According to the literature review, what would be the appropriate analytic approach to use?

In this essay, in conformity with the reasoning of von Schnurbein et al. (2016) and Leisinger (2008, corporate philanthropy is considered to be a managerial practice that is independent of the CSR concept. The distinction between the two concepts allows for a field of study to be developed where knowledge of corporate philanthropy is differentiated from that of CSR. In this way, as Ashford and Gibbs (1990) propose, the theoretical framework used in this study, to holistically analyze the concept of corporate philanthropy, is the theory of legitimacy. A classic theory stemming from organizational sociology that allows for the development of a perceptual vision of the phenomenon.

Corporate philanthropy as a legitimization strategy

The involvement of private companies in corporate philanthropy has been gradually increasing over the past few years (Volpentesta, 2016; Weeden, 2015). On the one hand, Tsang et al. (2009) state that private companies are more and more conscious of their capacities as agents of change for the communities in which they operate. On the other hand, companies are taking into consideration the impact they have on society because of the growing expectations of their stakeholders from a social and environmental point of view (Ahmad & Tower, 2009). From this perspective, the theory of legitimacy is interested in the relationship between business and society and proposes an alternative point of view to the concept of corporate philanthropy (Chen et al., 2008).

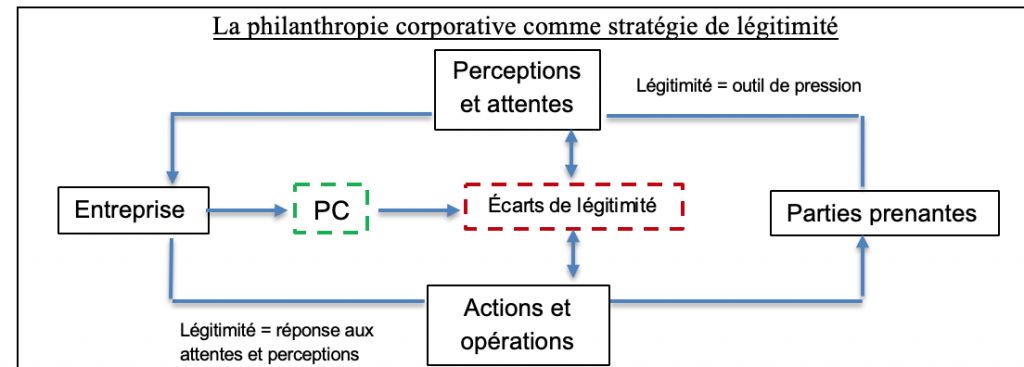

The theory states that a company cannot exist in isolation, as it must constantly be in relation to society. According to Suchman (1995, p. 574), legitimacy is defined as: “the generalized perception that the actions of an entity are desirable and/or appropriate in a social construct of norms, values, beliefs and definitions”. So, private companies are seen as legitimate when their objectives, functioning and impact are in line with stakeholder expectations (Lindblom, 1994).In other words, organizational legitimacy represents the two-directional relationship between companies and their stakeholders (including society in the larger sense). From a managerial perspective, legitimacy represents the management of stakeholder perceptions and expectations process that concerns the actions, operations and impacts of companies (Lawrence et al., 1997). Companies must thus carefully respond to perceptions and expectations in order to avoid damaging their image or reputation. From the stakeholder’s perspective, legitimacy is a pressure tactic on private companies and industries that corrects or changes actions and operations that are not desirable for society (Lawrence et al., 1997). If a stakeholder manages to convince other stakeholders to change their perceptions or to reconsider their expectations towards a company, it is likely that the latter be forced to implement the desired changes in their actions or operations. The differences between the actions and operations of private companies and the expectations and perceptions of stakeholders are deemed “legitimacy gap” (Sethim 1979). The latter directly impact the legitimacy of companies. In order to reduce or remove the gaps, private companies can resort to corporate philanthropy practices to improve their social legitimacy (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Corporate philanthropy as a legitimacy strategy – Own conceptualization

To be more precise, corporate philanthropy, as a legitimization strategy, solely responds to the forms of organizational legitimacy presented by Boutilier and Thomson (2011), meaning economic and sociopolitical legitimacy. Economic legitimacy occurs when stakeholders perceive the company to be acting in order to award themselves with an economic benefit. Sociopolitical legitimacy is when stakeholders perceive the company’s actions as contributing to the well-being of communities, respecting local norms, satisfying social expectations and demonstrating equity and justice (Boutilier et Thomson, 2011).

To conclude, through the legitimacy theory, corporate philanthropy can be analyzed in a holistic manner. This theory allows for the simultaneous consideration of stakeholder perceptions and expectations and company actions. Given the growth of the phenomenon, as well as the current state of the research field, we consider that this approach is particularly apt for the development of new knowledge.

On this aspect, we see three significant developments. The first has to do with the dynamics and processes that lead philanthropists to shift from corporate philanthropy to grantmaking philanthropy. Little literature has been found on the subject: there is thus a whole field of research that is possible. The second development is regarding the relationship that can be found between philanthropists, grantmaking philanthropy and entrepreneurs. This relationship is neither studied nor considered to be the responsibility of grantmaking philanthropy actors. However, it directly concerns both the dimensions of corporate philanthropy and corporate social responsibility. Once again, research in this direction would allow for a better vision of how corporate philanthropy and CSR could enable better integration of corporations into society.

Translation by Katherine Mac Donald