Ways of doing, knowing, connecting and being: Connecting students to respectful Indigenous community research and projects

Land Acknowledgement

This paper would not have been possible without collaborating with various Indigenous communities, students, and Indigenous-led and focused, non-profit organizations. In the article, we highlight an international Indigenous Studies course delivered at the University of Calgary. The University of Calgary is situated in Treaty 7 territory, in the City of Calgary which is known to the Blackfoot as Moh-kins-tsis, the Tsuut’ina as Guts’ists’I, and the Stoney Nakoda as Wîchîspa. In the spirit of respect, reciprocity and truth, we honour and acknowledge the Blackfoot Confederacy ‒ comprising of the Siksika, Piikani, and Kainai First Nations ‒ as well as the Tsuut’ina First Nation, and the Îyâxe Nakoda including the Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nations. We acknowledge that this territory is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3, within the historical Northwest Métis homeland. Finally, through our work and intentions, we strive to honour and celebrate the land, the four-leggeds, the swimmers, the winged ones and the plant people and all the diverse Nations with whom we were able to co-create this knowledge.

Introduction

The goal of this article is to describe a community-based experiential learning opportunity that was created in collaboration with Indigenous and Indigenous-focused organizations and communities. With an emphasis on service, reciprocal learning and mutual respect, students engaged with community as equal learning partners. The emerging model is fostered through organization-academic partnerships that strive to provide the benefits of work-integrated learning for students in the International Indigenous Studies program at the University of Calgary as well as to the partnering organizations and communities. We describe our framework for community-driven experiential learning during the first iteration of the course, as ways of doing; the pedagogical approach as ways of knowing; and, what we learned from our partners as ways of connecting and being. The vision for the course is embedded in serving and supporting Indigenous communities and Indigenous peoples while adhering to ii’ taa’poh’to’p, the University of Calgary Indigenous strategy (ii’ taa’poh’to’p, 2017).

Ways of doing – Community driven experiential learning

ii’ taa’poh’to’p describes ways of doing as respectfully following cultural protocols, inclusion and representation of Indigenous people and communities (2017, p. 20). This article presents applied research that uses new and existing knowledge to provide support for initiatives through practical application. The experiential learning course is built around student projects that work with, by and for Indigenous-focused organizations, non-governmental organizations and Indigenous communities. The focus is on exploring Indigenous, parallel, blended, and applied research methods while honouring community protocols. Students applied ethical approaches to working with Indigenous peoples, organizations, and communities throughout their projects. Each applied project aimed to respectfully work with Indigenous communities and related organizations to help find practical solutions and build relevant services by using community-based and community-led approaches.

The majority of the students in this course were Indigenous and came from diverse backgrounds, with various lived experiences, from Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, and from a multitude of age groups and educational fields and as a result were able to apply diverse, unique and valuable perspectives to their projects (for a brief description of student projects see here). The class was also supported by two research coaches, who were the senior undergraduate students and authors of this article with extensive research experience. The research coaches were able to connect with students at the undergraduate level as well as share their experience-based research knowledge. The various levels of student involvement offered multi-level learning, opportunities for knowledge co-creation, learning by doing and teaching experiences.

Opportunities for experiential learning, especially for students in programs that do not have access to co-op, internships, or community-based learning, can create essential bridges between academic knowledge and professional or community-based knowledge. Practical applications of theoretical knowledge, active participation due to the immersion in experiential learning opportunities and greater understanding of community and social frameworks have been identified as positive impacts of experiential learning (O’Connor, 2010). Indigenous pedagogy values the ability to learn independently through observation, and by listening and participating with minimum intervention or instruction, essentially learning by seeing and doing (Battiste, 2002). Experiential and place-based learning is integral to Indigenous teaching methodologies and has been identified as a major factor for greater autonomy and self-determination for Indigenous students and communities (O’Connor, 2010). Battiste (2002) urges educators to experiment with teaching methods to connect with the multiple ways of knowing.

Community-integrated experiences within Indigenous Studies, that follow respectful, reciprocal, relevant and responsible approaches, can bridge a critical gap between the needs of communities and the experiential learning needs of Indigenous and non-Indigenous students (McGregor et al., 2018). Most student projects and presentations included reflections on how to work toward reconciliation. One outcome of the student reports included research findings that were then used to make changes to decolonize existing policies (Caldwell et al., 2015).

Knowledge co-creation embedded within a community participatory research model has the potential to positively impact researchers and Instructors as well as research participants and involved organizations and communities (Banks et al., 2017). Students who engage with community-integrated learning opportunities develop equitable relationships, practice cultural humility, expand their awareness of how research can negatively and positively impact communities, and learn how to engage respectfully with community members (Costigan, 2020). Indigenous Studies courses lend themselves to critically examine how research has affected Indigenous people and communities and encourage students to question their definition of research.

Ways of knowing – Pedagogical approach

“Indigenization… seeks to complement, improve, and share a different approach to the western perspective by giving a window into research from the Indigenous standpoint” (Student quote)

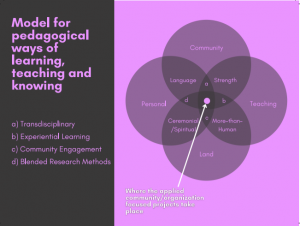

ii’ taa’poh’to’p explains that ways of knowing, “are sustained and expressed through languages, community traditions, protocols, and philosophies such as the recognition of the interconnectedness between humanity (past, present, and future), creation, and the cosmos (ii’ taa’poh’to’p, 2017, p. 15). The pedagogical approach for this course aligns with the bold statement that, “by ‘learning with each other while we are doing,’ there is no expert, there is no researcher, there are only people working and learning together on our personal peace journeys to improve the lives of our community” (Cormier & Ray, 2018, p. 113). The multilayered connections presented in Figure 1 describe the relationships that lead to successful student projects by applying pedagogical ways of learning, teaching, knowing, and doing. The outer overlapping layer consists of community, teaching, land, and the personal, which then overlap with ceremony, language, strength, and the more-than-human. Ways of doing can be described as community-led and engaged, transdisciplinary, including experiential learning, and following Indigenous, blended, or parallel research methods (McGregor et al., 2018).

Figure 1

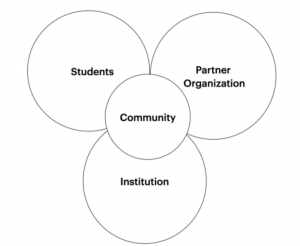

The projects included community members, student participants, the academic institution (including support from the Office of Indigenous Engagement), as well as organizational partners (Figure 2). The goal is to support Indigenous community-driven initiatives with the aim of working in true partnership that is led or envisioned by the community through: valuing and supporting the identity of the community; building on existing community strengths; cultivating reciprocal relationships between community partners and academia during each stage of the project, understanding that data and results are community-owned; and translating research results into action as directed by the community.

Figure 2: Collaborators supporting community-initiated projects

One consistent and recurring theme throughout the course was the importance of knowledge co-creation and equitable collaboration (please refer to the First Nations Information Governance Centre for the First Nations Principles of OCAP). Students were guided to thoughtfully build reciprocity into their work and to follow the principles of OCAP that specify that data belongs to the community and that the community decides how to use project results. The co-creative knowledge building process stives to acknowledge and honor community partners, Elders and knowledge keepers. For example, all collaborators should be considered equal authors in potential publications.

This pilot course was launched virtually during the pandemic; therefore, all relationships were virtual as was the delivery of course content. It is expected that in-person delivery will foster different experiential learning opportunities for students and continue the ongoing, meaningful, and genuine relationships with communities. Our hope is that the framework and experiences presented here contribute to learning models in community-based courses.

Ways of connecting and ways of being – learning from partners

“We must listen if we want to understand the needs of others. Listening, acknowledging, and actively seeking change must be constants when looking to better current practices. Indigenous students know best what…they require, and it is time we listened” (Student quote).

ii’ taa’poh’to’p partly describes ways of connecting and ways of being as working toward transforming current policies and practices to center land, the more-than-human and humanity’s relationship with land. The student projects aligned with respectful partnerships between the University of Calgary and Indigenous communities and “emphasize[d] service by interacting with communities as equal learning partners” (ii’ taa’poh’to’p, 2017, p. 24).

The first two sentences of the student quote opening this section highlight the importance of listening and decolonizing learning while working with community partners. New relationships and connections were formed among students, organizational partners, Indigenous communities, and the academic institution. The student projects created opportunities to learn how to support community-initiated work together, in a respectful way, and provided valuable lessons on how to continue to move forward together.

The collaborative work between both the students and the partners offered community organizations the opportunity to explore an area of research that may not have otherwise been completed. All students compiled and presented a project report, written for the community and with the intention to serve and benefit the community. As the students worked on the projects, the organizations formed relationships with students and this, in turn, led to potential employment prospects for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. Furthermore, this experiential learning provided opportunities for the students that included engaging professionally with on-the-ground organizations.

One component of the University of Calgary strategic plan is a focus on community engagement through collaborative partnerships and community service (Eyes High Strategy, 2017, p. 15.). If approached with good intentions; with knowledge of appropriate Indigenous community protocol; and with institutional support; community-based participatory research can be effective in building and fostering trusting relationships between the community, academic institutions and faculty. However, we acknowledge that engaging in community-based participatory research requires a substantial commitment to Indigenous community organizations; therefore, it is paramount to ensure they are not overburdened by the partnership. Careful planning, acquiring funding and various levels of support from the institution and faculty members are needed to prioritize involved Indigenous communities and their needs. Ensuring the continuity of relationships is also vital. Indigenous and non-Indigenous community-based organizations are limited by their capacity to support this work and ultimately institutions and faculty members are responsible for supporting collaborations. Organizations have unique goals, timelines and additional pressures, and it is important to be mindful of their capacity and resources to support such partnerships and projects. Relationships were formed with each partner and organization to ensure each student project was appropriate, benefited the community and was not diverting resources from the community. Ongoing relationships, reciprocity and open communication are key to continuing to respectfully work on Indigenous focused projects.

To work towards decolonization and reconciliation and to build an applied learning model into student learning, it is crucial to continue to foster relationships with Indigenous communities in a respectful way. There is a need to work toward the eradication of harmful research practices that exploit marginalized communities. Academics, researchers, and students have a responsibility to ensure that co-created knowledge remains, serves and benefits communities. If community-campus engagement is considered an institutional priority, institutions have a responsibility to provide the resources needed to support community-based courses and experiential learning projects.

Funding Acknowledgement

The research coaches were funded by the Course-based Undergraduate Research Experience (CURE) opportunity under the Taylor Institute of Teaching and Learning. This course was also indirectly supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) through the supervision and collaboration with other academics. We are grateful that the next iteration of the course will be funded through CEWIL Canada. We are very grateful to Shawna M. Cunningham, Director of Indigenous Strategy, at the University of Calgary, for her helpful review and comments on an earlier draft of the article.

Madeleine Brulotte holds a bachelor of Kinesiology and has been pursuing a Bachelor of Biological Sciences degree at the University of Calgary. She was a Research coach for the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning, working alongside Dr. Adela Kincaid and Jasleen Brar in the Indigenous 502 course.

Saskia Livingstone is currently in her final semester of her Bachelor of Law and Society at the University of Calgary. As a recipient of PURE Undergraduate research awards, she has been working as a research assistant over the summer exploring animal-human relationships through Indigenous methodologies and land-based learning. She is currently a research coach for the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning, working alongside Dr. Adela Kincaid in the UNIV 302 course focusing on humans, animals and the environment.

Saskia Livingstone is currently in her final semester of her Bachelor of Law and Society at the University of Calgary. As a recipient of PURE Undergraduate research awards, she has been working as a research assistant over the summer exploring animal-human relationships through Indigenous methodologies and land-based learning. She is currently a research coach for the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning, working alongside Dr. Adela Kincaid in the UNIV 302 course focusing on humans, animals and the environment.

Jasleen Brar is currently a Bachelor of Health Sciences student at the University of Calgary with a major in Health and Society and minor in Indigenous Studies. She has been working as a research student for the past few years under the Department of Family Medicine, researching the barriers to primary healthcare for immigrant and refugee women, and recently under the Department of International Indigenous Studies, evaluating and building local community partnerships. Jasleen is also an avid community volunteer with extensive experience working with and for local immigrant communities within the realms of advocacy, service and healthcare.

This article is part of the special edition of September 2021: Respectful community engaged research. You can find more information here