By: Miranda Ivany, Atlantic Hub

Mitigating environmental issues has become an increasingly important topic in the political realm, community and regional development, and sustainability-related issues. All government levels have attempted to shape the trajectory of environmental concerns through an array of policies, legislation that designates protected areas, and program funding (Carter & Ross, 2014; Gelissen, 2007; Grandy, 2013). However, scholars suggest that the extent to which these efforts succeed ebbs and flow with the day’s economic context and political tone (Carter & Ross, 2014; Gelissen, 2007; Gamble, 2014; Grandy, 2013). In many instances, communities have witnessed the emergence of grassroots efforts by not-for-profit and charitable organizations to mitigate significant environmental concerns. The wicked nature of environmental and sustainability issues acknowledges the necessity of increasing government, business, not-for-profit, and civil collaboration (Akamani, 2016; Vodden et al., 2013).

Environmental philanthropy is defined as providing time, money, or gifts to mitigate environmental issues (Carter & Ross, 2014; CEGN, 2018; Greenspan et al., 2012; Lutter, 2010). It is described as one type of environmentally conscious behaviour enacted by individuals, communities, and organizations. Examining the associations between different types of intention to donate, Greenspan et al., (2012) found that a person’s value-orientation, political orientation, environmental knowledge, gender, and academic status all contribute to whether they will adopt environmental philanthropic behaviours.

Between 2006 to 2015, environmental charities felt the chilling political effects of Canada’s conservative administration led by Stephen Harper. Within this period, Harper’s administration made hundreds of millions of dollars worth in cuts to environmental funding and supporting regulations (i.e., cuts to Environment Canada, Oceans and Fisheries Canada) (Nelson, 2011). MacNeil (2013) writes that the federal government deemed many environmental charities as ‘radical,’ and in opposition to their development goals. During this time, the government increased the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) funding for the auditing and oversight of environmental charities, resulting in the increased policing of their activities. As a result of the shift in government ideals, many environmental charities in Canada faced deregistration (MacNeil, 2013; Wellstead, 2018). Although this period of political conservatism left a lasting impression on Canada’s environmental charities, charities throughout the country have continued to carry out work that positively affects their communities.

The literature on environmental philanthropy contends that paradigms of thought have shifted away from conceptualizations, which separate the environment from its social components towards approaches that recognize the intersection of current socio-cultural and environmental issues (CEGN, 2018; Lutter, 2010; Secord, 2014). An emerging consensus posits that how we conceptualize solutions to environmental challenges must be reflected in multifaceted funding structures, effectively harnessing interdisciplinary approaches to acknowledge how intimately tied many funding issues, in reality, are (CEGN, 2018; Lutter, 2010; Secord, 2014). These approaches must address environmental conservation and extend to our economic, health, and social sectors (Lutter, 2010).

Environmental Philanthropy Across Canada

In 2016, the Canadian Environmental Grantmakers’ Network (CEGN) conducted a systematic review of the state of environmental philanthropy across Canada. CEGN’s report analyzed 3304 grants totalling $116.5 million [1].

It was found that the top five most funded environmental issues were: (1) biodiversity and species protection; (2) coastal and marine ecosystems; (3) freshwater ecosystems; (4) terrestrial ecosystems and land use and; (5) energy. Additionally, it was found that the top five strategies employed by environmental organizations were: (1) direct activity; (2) education; (3) research; (4) public awareness-raising and; (5) capacity building.

Charities that champion environmental causes tend to receive a smaller portion of the total annual charitable donations from environmental funders compared to charitable organizations that carry out health and education-related activities (CEGN, 2018; Gamble, 2014; Turcotte, 2015). A review of the distribution of environmental grants from environmental funders (i.e., foundations) undertaken by CEGN.

Charities that champion environmental causes tend to receive a smaller portion of the total annual charitable donations from environmental funders compared to charitable organizations that carry out health and education-related activities (CEGN, 2018; Gamble, 2014; Turcotte, 2015). A review of the distribution of environmental grants from environmental funders (i.e., foundations) undertaken by CEGN.

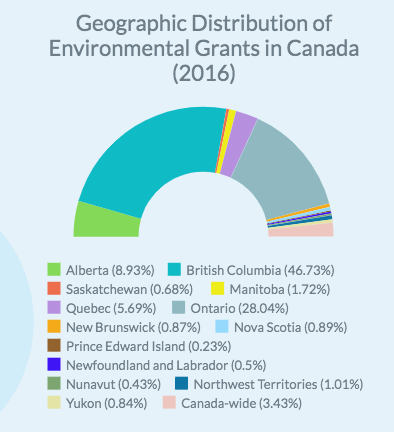

The CEGN review found that British Columbia and Ontario are the most funded regions in Canada (receiving 75 percent of all grants, equalling $80.5 million). In contrast, in total, the Atlantic provinces received only 2.5 percent of environmental grants (note* total funding dollar amounts were not stated for Atlantic Canada) CEGN, 2018; Gamble, 2014; Gelissen, 2007). Environmental charities in Atlantic Canadian provinces receive the smallest portion of charitable grants (from environmental foundation funders) earmarked for environmental causes in all of Canada (CEGN, 2018; Gamble, 2014). The question remains whether these statistics tell us that environmental issues in Atlantic Canada are considered less critical or if the figures are skewed by population and the relatively small number of total environmental charities and not-for-profits that exist in NL and Atlantic Canada.

Identifying ‘environmental’ charities in NL and Atlantic Canada has proven to be a significant challenge. The available CRA codes which charities must categorize their activities under do not fully capture the work being done by environmental charities. Thus, to identify environmental charities in NL required a systematic scan of all resisted charities in the province. This scan revealed only 11 registered charities in NL that primarily carry out environmental activities. Further, the focus of the environmental work which these charities undertake is broad (e.g. education, awareness-raising, conservation).

Challenges & Opportunities

Research that addresses the challenges faced by environmental charities in NL and Atlantic Canada remains limited. Gamble (2014) highlights that some of the challenges faced by rural environmental charities in the Atlantic region include: (1) difficulty reaching a wide audience- making the process of receiving grants or individual donations more challenging; (2) limited internal and fundraising capacity; (3) a narrow focus of issues and; (4) lower levels of philanthropic wealth.

Furthermore, Gamble (2014) suggests that to combat these underlying issues, environmental charities and not-for-profits need to focus on strengthening network-building strategies to allow environmental charities to harness greater collective power. Moreover, he suggests that it will be important to expand the potential for environmental giving for environmental organizations in Atlantic Canada to broaden the narrative of their work. Gamble (2014) argues that broadening narratives will highlight how the environmental issues that the organization’s champion more broadly connect with challenges faced by other vital sectors in the province, such as health care and the economy.

Despite the recent experiences within the NL environmental charitable context (i.e. relatively low numbers of environmental charities, a smaller proportion of environmental grants received in NL than other regions in Canada), there are opportunities within this region. What makes Atlantic Canada, more specifically, NL, an interesting case to study the potential for environmental philanthropic growth, along with the challenges and opportunities that impact this potential, is the strong propensity of Atlantic Canadian residents’ to support charities in their home regions. Donor rates were found to be higher in Atlantic Canada compared to the rest of the country. Additionally, NL stood out considerably, with the highest charitable donor rate in all of Canada (87 percent) in 2013 (Turcotte, 2015). Additionally, NL residents were found to have the most heightened sense of belonging to their province and local communities (Statistics Canada, 2015).

Unanswered questions remain around the potential benefits these circumstances can produce in rural regions and whether or not the longstanding history of these rural areas’ resource economies might affect the growth of environmental philanthropy in rural NL (Hayter & Barnes, 2001). Further research is required to understand the disconnect between why the rate of giving in NL is so high while the number of charities, specifically in rural regions, is so low.

For additional information and statistics that look more broadly at the state of charities in Newfoundland and Labrador and Atlantic Canada, please see the webinar we hosted through the Atlantic Hub of PhiLab.